UML-06: Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Learning Objectives

After reading this post, you will be able to:

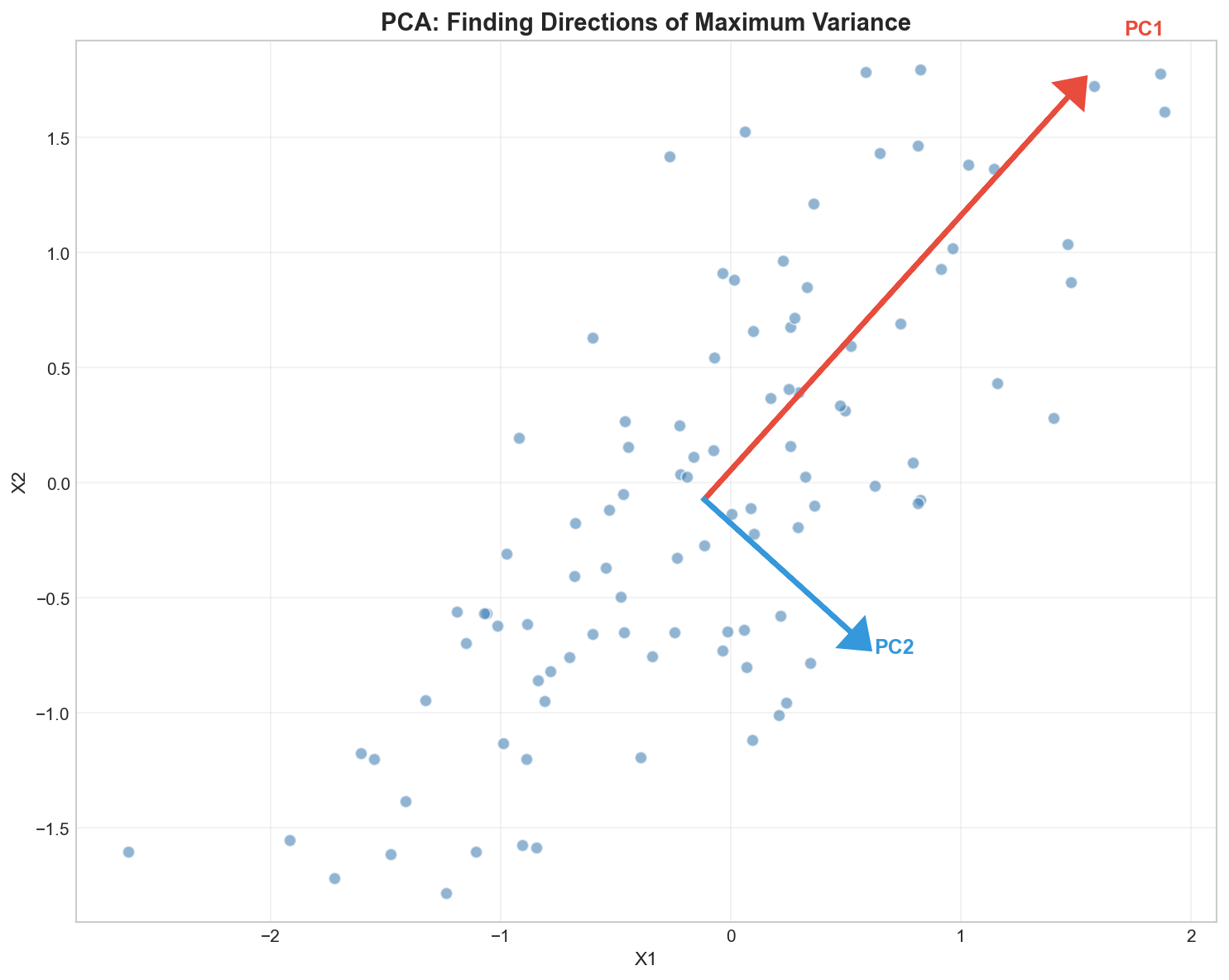

- Understand PCA as finding directions of maximum variance

- Perform dimensionality reduction for visualization and compression

- Interpret explained variance and choose the number of components

- Know when PCA helps and when it fails

Theory

The Intuition: The Photographer’s Challenge

Imagine you are trying to take a photo of a complex 3D object (like a teapot) to put in a catalog. You can only print a flat 2D image, but you want to show as much detail as possible.

- Bad Angle: Taking a photo from directly above might just look like a circle (lid). You lose all the information about the spout and handle.

- Best Angle (PC1): The angle where the teapot looks “widest” and most recognizable. This captures the maximum variance (detail).

- Second Best Angle (PC2): An angle perpendicular to the first one that adds the next most amount of unique detail (e.g., depth).

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is mathematically finding these “best camera angles” for your hyper-dimensional data.

The Math Behind PCA

Step 1: Center the Data

Subtract the mean from each feature: $$\tilde{X} = X - \mu$$

Translation: “Centering the subject.” Before taking a photo, you move the camera so the object is dead center in the viewfinder. If you don’t do this, the “best angle” might just be pointing at the center of the room instead of the object itself.

Step 2: Compute Covariance Matrix

$$C = \frac{1}{n-1} \tilde{X}^T \tilde{X}$$

Translation: “Measuring the spread.” We look at how features vary together. Do height and width increase together? This matrix captures the “shape” of the data cloud.

Step 3: Eigendecomposition

Find eigenvalues $\lambda_i$ and eigenvectors $v_i$ of $C$: $$C v_i = \lambda_i v_i$$

Translation: “Finding the axes.”

- Eigenvectors ($v_i$): The Direction of the camera angle.

- Eigenvalues ($\lambda_i$): The Amount of Detail (Variance) seen from that angle.

Step 4: Project Data

Sort eigenvectors by decreasing eigenvalue and project: $$Z = \tilde{X} W_k$$

Translation: “Taking the snap.” We rotate the data to align with these new best angles and flatten it onto the new 2D plane (the photo).

Explained Variance

The explained variance ratio tells us how much information each component captures:

$$\text{explained variance ratio}_i = \frac{\lambda_i}{\sum_j \lambda_j}$$

Choosing Number of Components

Common strategies:

| Strategy | Rule |

|---|---|

| Variance threshold | Keep enough for 90-95% variance |

| Elbow method | Look for drop in scree plot |

| Kaiser criterion | Keep components with eigenvalue > 1 |

| Cross-validation | Choose based on downstream task performance |

The Trade-off: Simplicity vs. Detail

Choosing $K$ is always a trade-off:

- Keep too few (Low $K$): You get a very simple, compressed photo, but you might lose important details (like the handle of the teapot).

- Keep too many (High $K$): You keep all the detail, but you’re back to the “Curse of Dimensionality” and store noise.

Guideline: Stop adding components when the next one adds mostly noise (the “Elbow” in the scree plot).

Code Practice

PCA on Iris Dataset

🐍 Python

| |

Output:

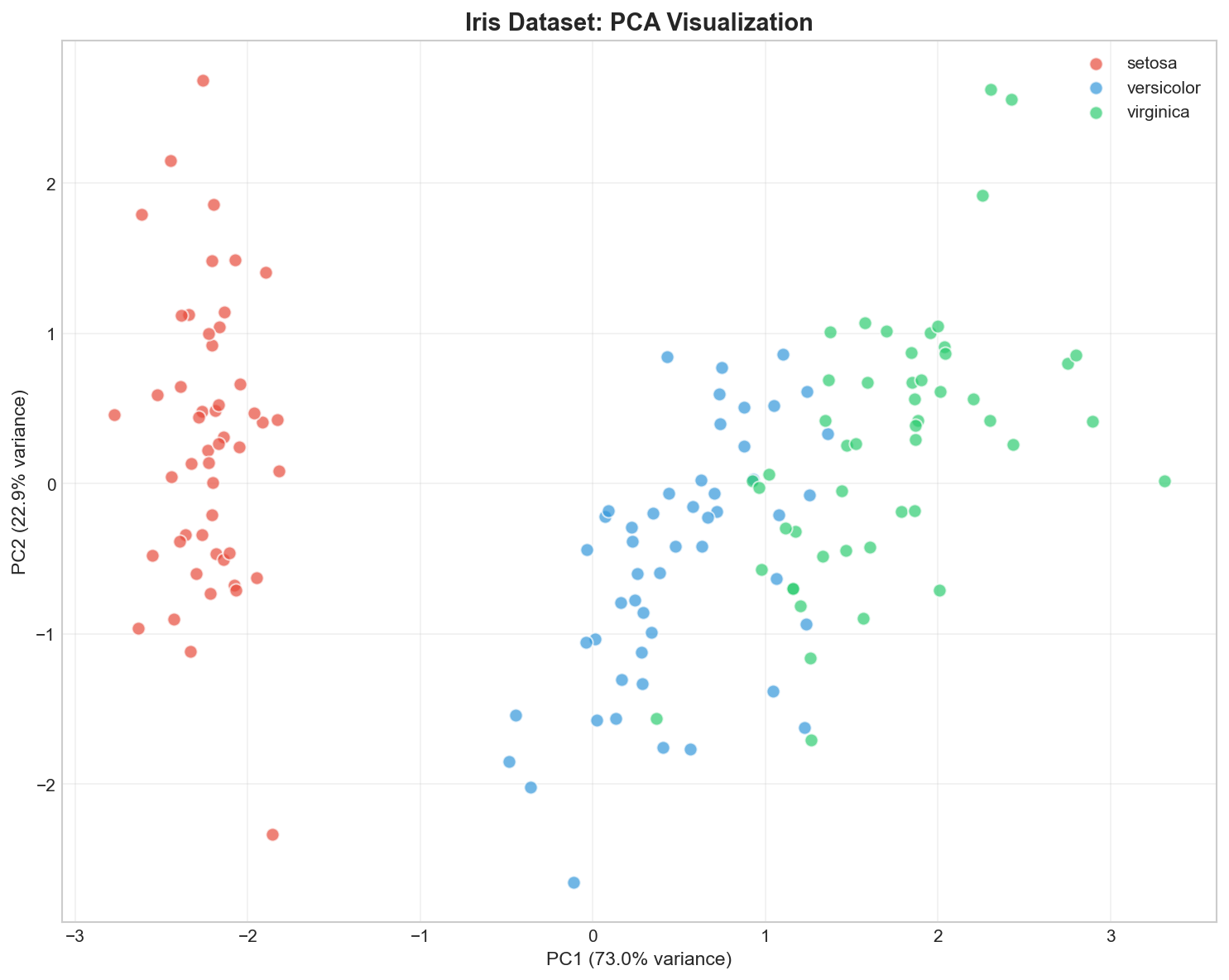

Visualizing in 2D

🐍 Python

| |

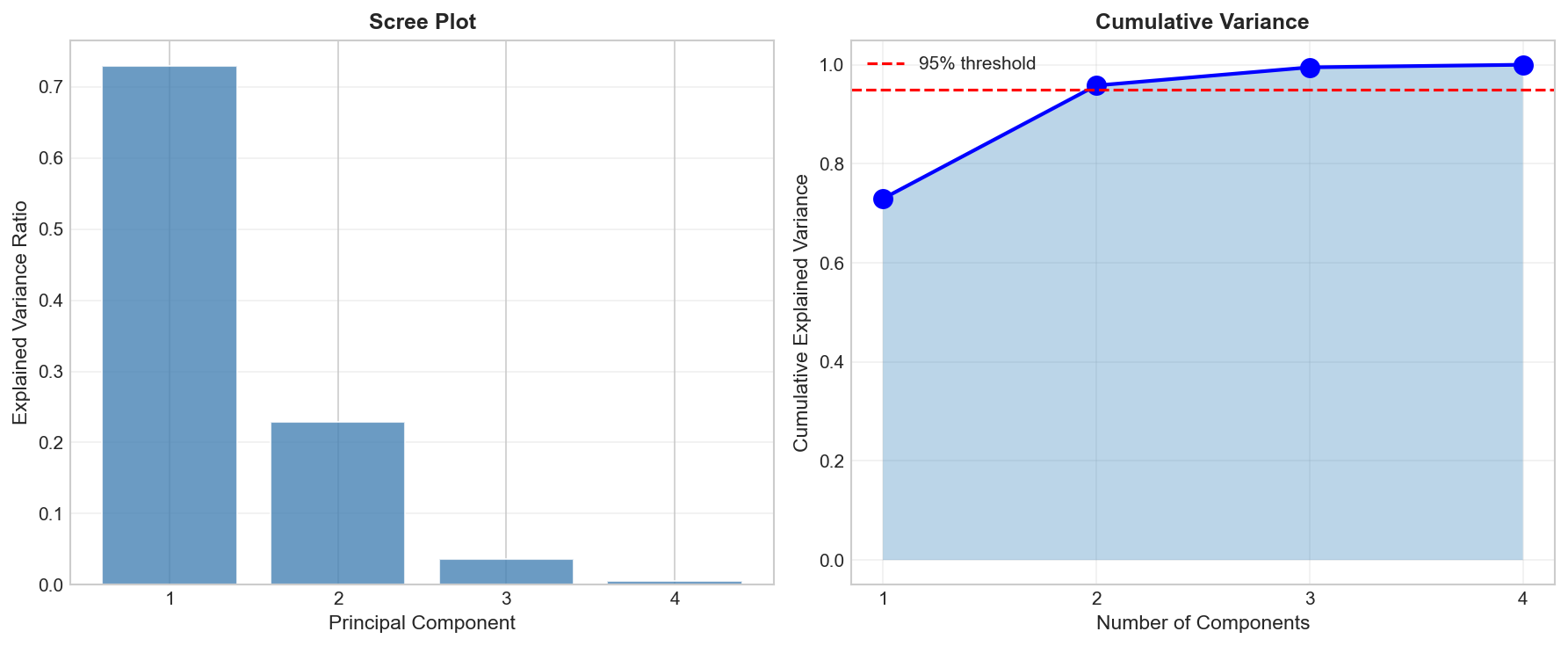

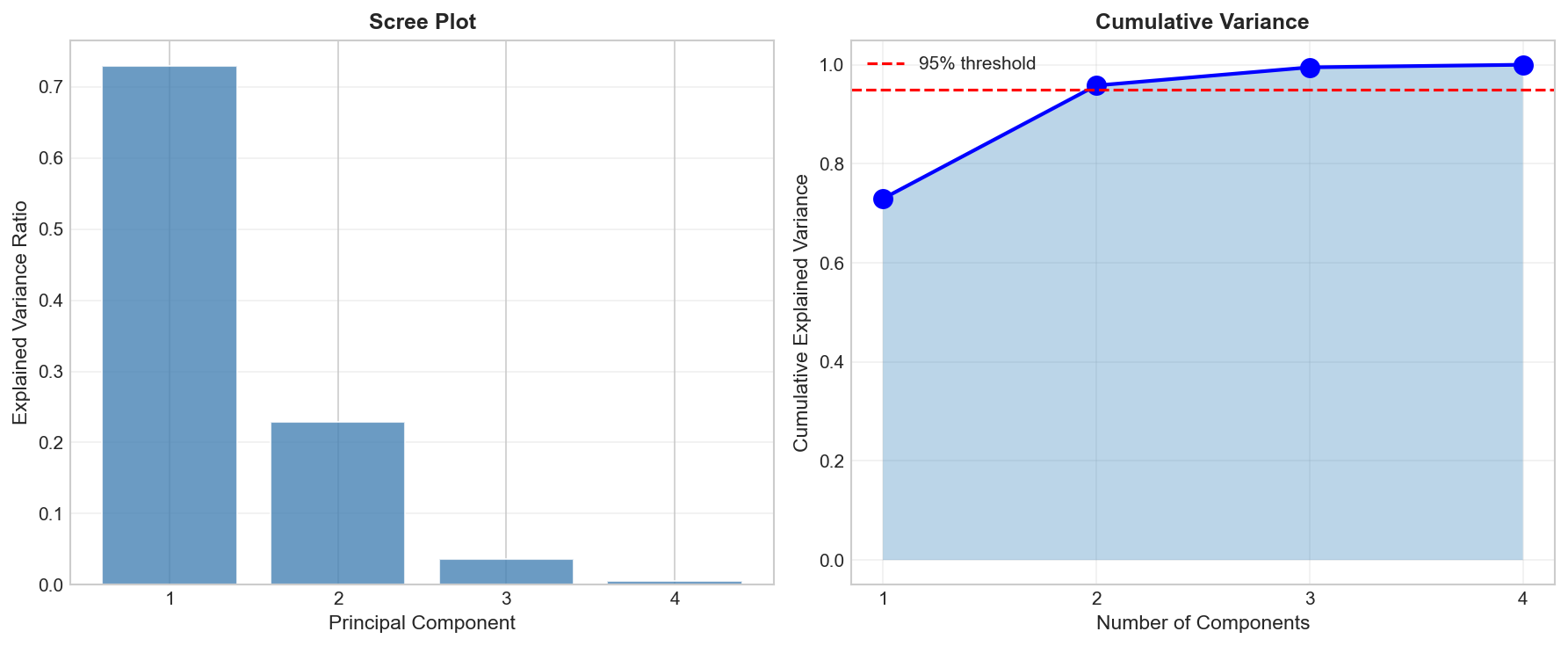

Scree Plot and Choosing Components

🐍 Python

| |

How to read this plot?

- The Elbow: Look for where the blue line levels off (after PC2).

- The Threshold: We want >95% total variance. PC1 (73%) + PC2 (23%) = 96%. Sufficient!

Understanding Principal Components

🐍 Python

| |

Output:

| |

Interpretation - The Recipe: Think of each PC as a recipe.

- PC1 is a mix of Petal Length (+0.58) and Width (+0.56). It essentially measures “Overall Size”.

- PC2 is mostly negative Sepal Width (-0.92). It measures “Sepal Narrowness”.

By projecting data onto PC1 and PC2, we are effectively graphing “Size” vs “Shape”.

PCA for Preprocessing

🐍 Python

| |

Output:

Interpreting the Results

- Full Features (4D): The model has access to every precise measurement.

- PCA (2D): The model is seeing a “flat photo” of the data.

- Result: Even though we flattened 4 dimensions into 2, we kept the important structure (95% variance), so the model still works perfectly. This proves the other 2 dimensions were mostly noise or redundancy!

Deep Dive

When PCA Works Well

| Scenario | Why PCA Helps |

|---|---|

| ✅ Linear correlations | PCA captures linear relationships |

| ✅ Visualization | Projects to 2D/3D |

| ✅ Noise reduction | Minor components often contain noise |

| ✅ Feature compression | Fewer dimensions, same information |

When PCA Fails

PCA limitations:

- Non-linear structure: PCA only finds linear projections

- Important variance ≠ useful variance: Variance may not correlate with class separation

- Interpretability: Components are combinations of features

- Scale sensitivity: Features must be standardized first!

PCA Variants

| Variant | Use Case |

|---|---|

| Kernel PCA | Non-linear dimensionality reduction |

| Sparse PCA | Interpretable, sparse components |

| Incremental PCA | Large datasets that don’t fit in memory |

| Randomized PCA | Fast approximation for large data |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Should I always scale before PCA?

Yes! PCA maximizes variance, so high-variance features dominate without scaling. Always use StandardScaler first.

Q2: Can PCA be used for feature selection?

Not directly — PCA creates new features (components), not selects original ones. For selection, use methods like L1 regularization or recursive feature elimination.

Q3: What if I need more than 95% variance?

The threshold is problem-dependent:

- Visualization: 2-3 components often enough

- Preprocessing: 90-99% depending on downstream task

- Compression: Balance quality vs. storage

Summary

| Concept | Key Points |

|---|---|

| PCA | Linear dimensionality reduction via eigendecomposition |

| Principal Components | Orthogonal directions of maximum variance |

| Explained Variance | Eigenvalue / total variance |

| Choosing K | Keep enough for 90-95% variance |

| Preprocessing | Always standardize features first |

| Limitation | Only captures linear structure |

References

- sklearn PCA Documentation

- Jolliffe, I.T. (2002). “Principal Component Analysis”

- “The Elements of Statistical Learning” by Hastie et al. - Chapter 14.5