MV-08: Continuous Systems – Strings, Bars, and Beams

In our journey so far, we have lived in a world of “lumps.” We modeled cars, buildings, and machines as discrete masses connected by weightless springs and dampers. This is called a discrete system. Whether it had one degree of freedom or one hundred, the number was finite.

But look at a guitar string. Or a transmission shaft. Or an airplane wing. These aren’t just lumps of mass connected by springs; the mass and elasticity are distributed continuously throughout the material. These are Continuous Systems (or distributed systems).

Because every infinitesimal point on these bodies can move, they theoretically possess an infinite number of degrees of freedom. Consequently, they have an infinite number of natural frequencies.

In this post, based on Chapter 8 of Rao’s Mechanical Vibrations, we will explore the wave equations that govern strings, bars, and shafts, tackle the complex fourth-order differential equations of beams, and learn how to estimate frequencies using Rayleigh’s Method.

The Vibration of Strings: The Wave Equation

The simplest continuous system is a tightly stretched string—like a violin string or an overhead transmission cable.

Consider a string of length $l$ under tension $P$. If we take a tiny element of length $dx$ and apply Newton’s second law, we don’t get a standard differential equation; we get a Partial Differential Equation (PDE) because the deflection $w$ depends on both position $x$ and time $t$.

The Governing Equation

The equation of motion for free vibration is the classic Wave Equation:

$$\boxed{c^2 \frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial x^2} = \frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial t^2}}$$

| Symbol | Physical Meaning | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| $w(x,t)$ | Transverse displacement | m |

| $c$ | Wave propagation speed | m/s |

| $P$ | String tension | N |

| $\rho$ | Mass per unit length | kg/m |

The wave speed is determined by the tension-to-mass ratio:

$$ c = \sqrt{\frac{P}{\rho}} $$

Frequencies and Mode Shapes

For a string fixed at both ends (like a guitar string), the boundary conditions are $w(0,t)=0$ and $w(l,t)=0$. Solving the PDE reveals that the string can only vibrate at specific Natural Frequencies:

$$ \omega_n = \frac{n\pi c}{l} = \frac{n\pi}{l} \sqrt{\frac{P}{\rho}}, \quad n = 1, 2, 3, \dots $$

Associated with each frequency is a Mode Shape—a sine wave pattern:

$$ W_n(x) = \sin \left( \frac{n\pi x}{l} \right) $$

| Mode | Shape Description | Nodes | Frequency Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| $n=1$ | Half sine wave | 0 (interior) | $1 \times f_1$ |

| $n=2$ | Full sine wave | 1 (center) | $2 \times f_1$ |

| $n=3$ | 1.5 sine waves | 2 | $3 \times f_1$ |

| $n=4$ | 2 full waves | 3 | $4 \times f_1$ |

Bars and Shafts: Same Equation, Different Physics

The wave equation isn’t unique to strings. Longitudinal vibration of bars and torsional vibration of shafts follow identical mathematics—only the physical quantities differ.

| System | Motion Type | Displacement | Wave Speed | Restoring Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| String | Transverse | $w(x,t)$ | $c = \sqrt{P/\rho}$ | Tension $P$ |

| Bar | Longitudinal | $u(x,t)$ | $c = \sqrt{E/\rho}$ | Young’s modulus $E$ |

| Shaft | Torsional | $\theta(x,t)$ | $c = \sqrt{G/\rho}$ | Shear modulus $G$ |

Effect of Boundary Conditions

The same wave equation produces different frequency spectra depending on the boundary conditions:

| Configuration | Natural Frequencies | Physical Example |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed-Fixed | $\omega_n \propto n$ (all integers) | Guitar string |

| Fixed-Free | $\omega_n \propto (2n-1)$ (odd only) | Diving board, skyscraper |

| Free-Free | $\omega_n \propto n$ + rigid body mode | Floating log |

Lateral Vibration of Beams: The Fourth-Order Challenge

The analysis complexity increases significantly when we move from axial to lateral (bending) vibration. Unlike strings that resist displacement through tension, beams resist through internal bending stiffness ($EI$).

The Euler-Bernoulli Beam Equation

The governing equation involves a fourth-order spatial derivative:

$$\boxed{\frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} \left[ EI \frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial x^2} \right] + \rho A \frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial t^2} = f(x,t)}$$

For a uniform beam in free vibration, this simplifies to:

$$ c^2 \frac{\partial^4 w}{\partial x^4} + \frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial t^2} = 0, \quad \text{where } c = \sqrt{\frac{EI}{\rho A}} $$

| Symbol | Physical Quantity | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| $w$ | Transverse displacement | m |

| $EI$ | Flexural rigidity | N·m² |

| $\rho A$ | Mass per unit length | kg/m |

| $c$ | Wave parameter | m²/s |

Why Four Boundary Conditions?

Since the equation is fourth-order in space, we need four boundary conditions (two at each end). This contrasts with strings and bars, which only need two.

| Boundary Type | Deflection ($w$) | Slope ($w’$) | Moment ($M = EIw’’$) | Shear ($V = EIw’’’$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinned | $= 0$ | Free | $= 0$ | Free |

| Fixed | $= 0$ | $= 0$ | Free | Free |

| Free | Free | Free | $= 0$ | $= 0$ |

Common Beam Configurations

| Configuration | Frequency Coefficient $\beta_n L$ | Real-World Example |

|---|---|---|

| Simply Supported | $\pi, 2\pi, 3\pi, \ldots$ ($n\pi$) | Bridge span, ruler on two supports |

| Cantilever | $1.875, 4.694, 7.855, \ldots$ | Diving board, aircraft wing |

| Fixed-Fixed | $4.730, 7.853, 10.996, \ldots$ | Welded beam, clamped pipe |

Rayleigh’s Method: The Energy Shortcut

Solving PDEs analytically for complex structures—tapered wings, variable cross-sections, or unusual boundary conditions—is often intractable. Rayleigh’s Method provides an elegant alternative: estimate the fundamental frequency using energy principles without ever solving the differential equation.

The Core Idea: Energy Conservation

During free vibration, energy continuously transforms between two forms:

| State | Kinetic Energy ($T$) | Potential Energy ($V$) |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum displacement | 0 | $V_{max}$ (all strain) |

| Equilibrium position | $T_{max}$ (all motion) | 0 |

Conservation of energy demands:

$$\boxed{T_{max} = V_{max}}$$

The Recipe

- Assume a mode shape $W(x)$ that satisfies the geometric boundary conditions

- Good choices: static deflection curve, polynomial, or trigonometric function

- Compute maximum kinetic energy: $T_{max} = \frac{1}{2}\omega^2 \int_0^L \rho A , W(x)^2 , dx$

- Compute maximum potential energy: $V_{max} = \frac{1}{2} \int_0^L EI \left(\frac{d^2W}{dx^2}\right)^2 dx$ (for beams)

- Equate and solve for $\omega$

Rayleigh’s Quotient

The result is a powerful formula that directly yields the frequency estimate:

$$ \omega^2 = \frac{\int_0^L EI \left(\dfrac{d^2W}{dx^2}\right)^2 dx}{\int_0^L \rho A , W(x)^2 , dx} = \frac{\text{Stiffness (curvature)}}{\text{Inertia (mass distribution)}} $$

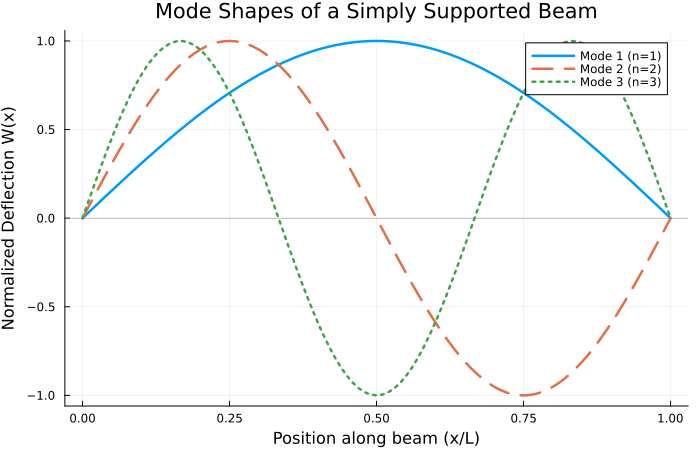

Julia Example: Plotting Beam Modes

Let’s visualize the first three mode shapes of a simply supported beam. The mode shapes are sinusoidal: $W_n(x) = \sin(n\pi x / L)$.

| |

Expected Output:

Summary

This post extended vibration analysis from discrete masses to continuous structures—systems with infinite degrees of freedom:

| System Type | Governing Equation | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Strings, Bars, Shafts | 2nd-order wave equation | Constant wave speed $c = \sqrt{T/\rho}$ or $\sqrt{E/\rho}$ |

| Beams (Euler-Bernoulli) | 4th-order PDE | Bending stiffness introduces dispersive waves |

| Boundary Conditions | Determine mode shapes | Fixed, free, pinned → different frequency formulas |

| Rayleigh’s Method | Energy-based estimation | Upper bound: $\omega_{est} \geq \omega_{exact}$ |

What’s Next?

How do we stop unwanted vibrations? The next post covers vibration control—isolation mounts, rotating machinery balancing, and dynamic vibration absorbers.

References

Rao, S. S. (2018). Mechanical Vibrations (6th ed.). Pearson.