The Art of Infinity: A Journey into the World of Fractals

“In the mind’s eye, a fractal is a way of seeing infinity.” — James Gleick

Picture this: you’re hiking through a misty forest and pause to examine a fern. Each tiny leaflet is a perfect miniature copy of the entire frond. Or imagine gazing at a satellite image of a coastline—zoom in, and the jagged edges look eerily similar to what you saw from orbit.

Welcome to the world of Fractals—shapes that repeat themselves at every scale. They are nature’s hidden geometry, the visual fingerprint of chaos, and living proof that infinite complexity can emerge from breathtakingly simple rules.

In this article, we’ll journey through the 9 major categories of fractals, from the hypnotic spirals of the complex plane to the wild unpredictability of chaotic attractors.

mindmap

root((Fractals))

Equation-Based

Complex Number Iterations

Strange Attractors

Geometry-Based

Geometric Recursion

IFS

L-System Curves

Tree Fractals

Simulation-Based

Cellular Automata

Random Fractals

Dimension

3D Fractals

What is a Fractal?

A fractal is a geometric object that exhibits self-similarity—zoom in on any part, and it looks remarkably like the whole. Unlike the smooth curves and straight lines of classical geometry, fractals are “rough” at every magnification.

What makes them truly fascinating is their fractal dimension: a coastline isn’t quite a 1D line, nor a 2D surface—it exists somewhere in between, with a dimension like 1.25. This “in-between” quality captures how fractals fill space in unexpected ways.

The most astonishing part? These infinitely intricate structures often spring from ridiculously simple iterative rules. Let’s explore how.

Exploring the 9 Categories of Fractals

Let’s dive into the different “flavors” of fractals, exploring one representative example from each of the 9 categories in this blog post.

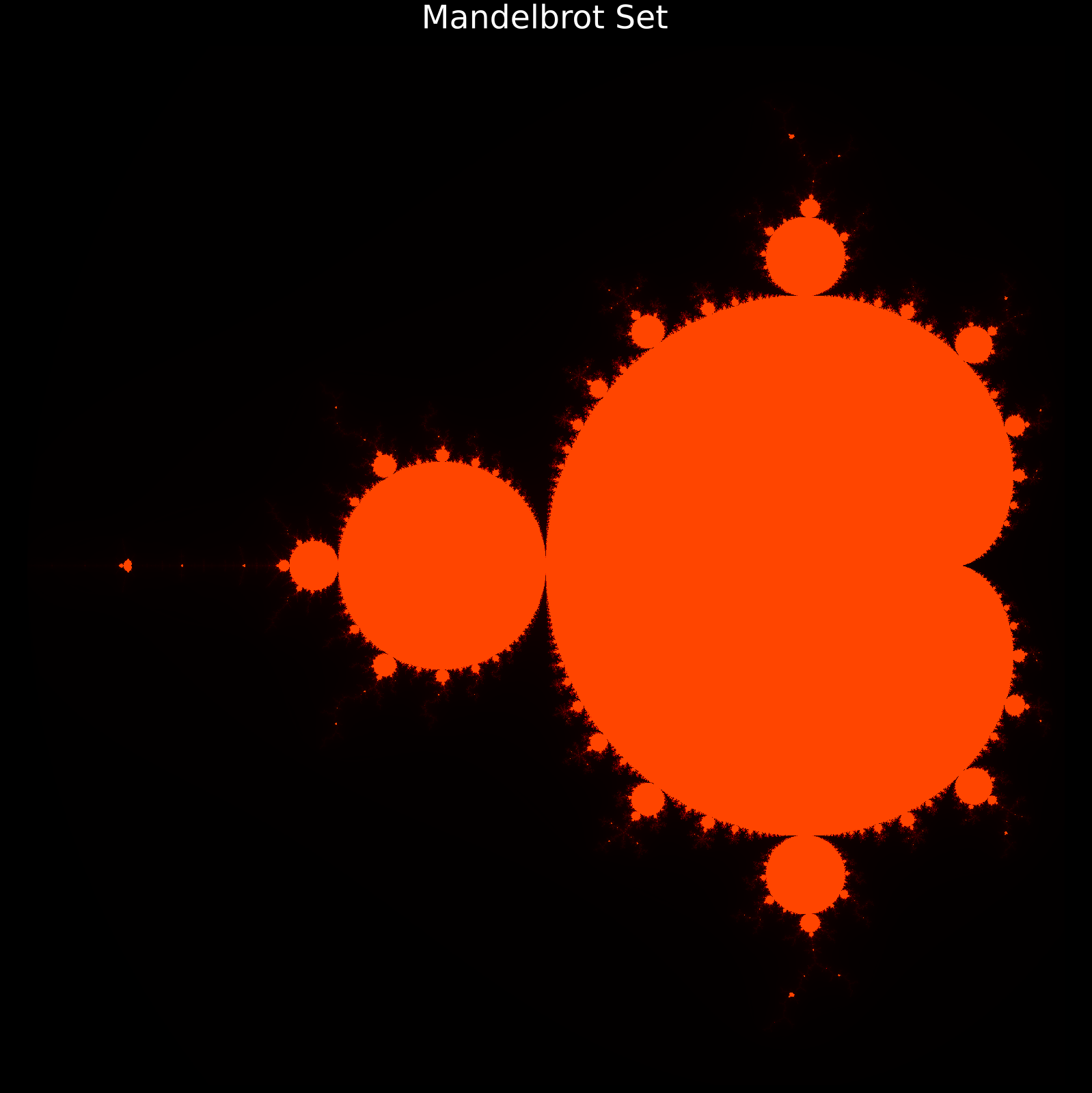

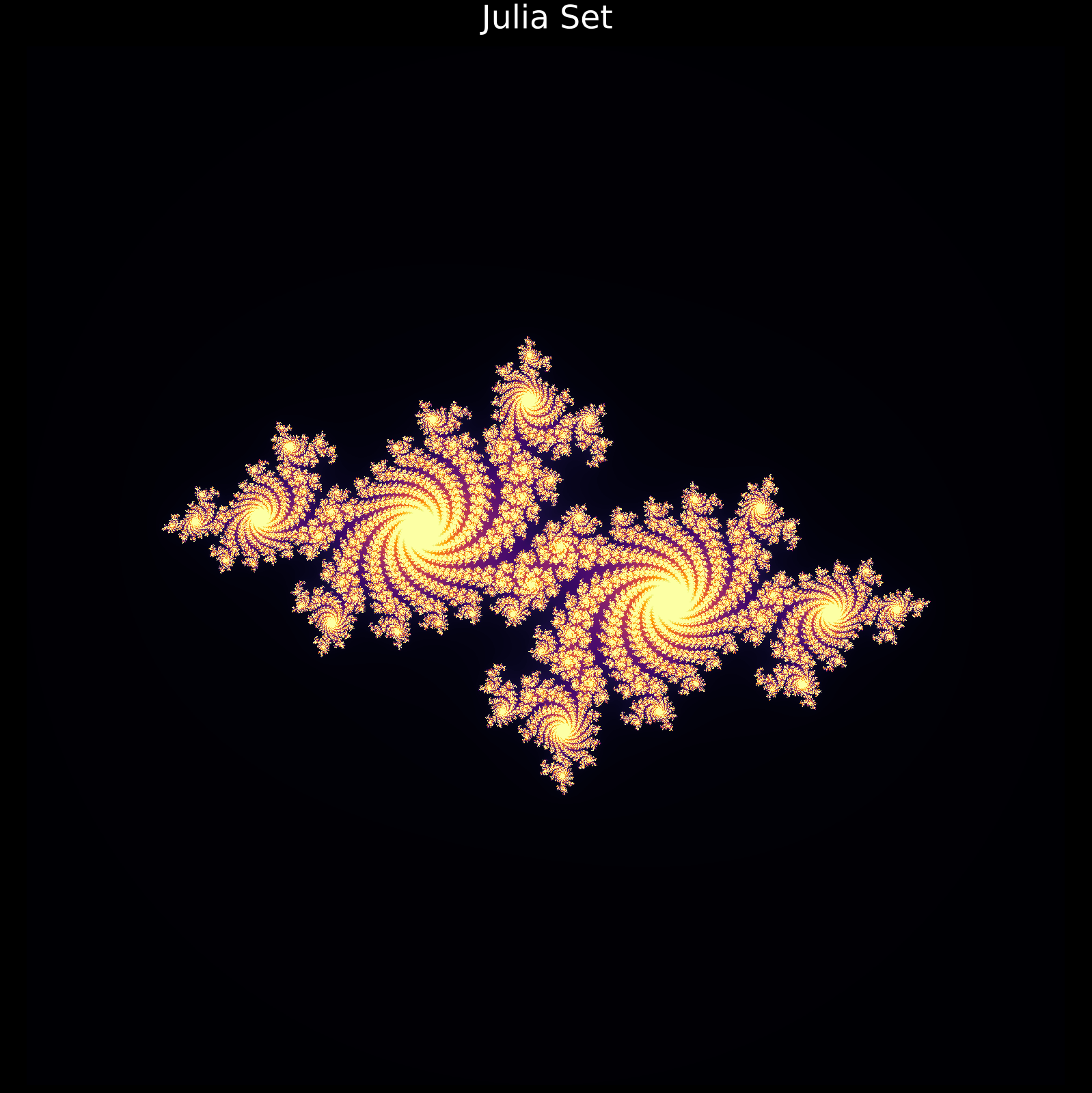

Complex Number Iterations

We begin with the rock stars of the fractal world—patterns born from iterating simple equations on the complex number plane. These fractals have graced countless posters, screensavers, and album covers.

The Mandelbrot Set

The icon of fractal geometry. It is generated by a deceptively simple equation: $$z_{n+1} = z_n^2 + c$$ As you zoom into the “edge” of the Mandelbrot set, you find spirals, seahorses, and even miniature copies of the entire set itself. It demonstrates how a deterministic formula can create infinite variety.

Geometric Recursion

Moving from equations to pure geometry, we find fractals built by a simple recipe: take a shape, transform it, and repeat forever.

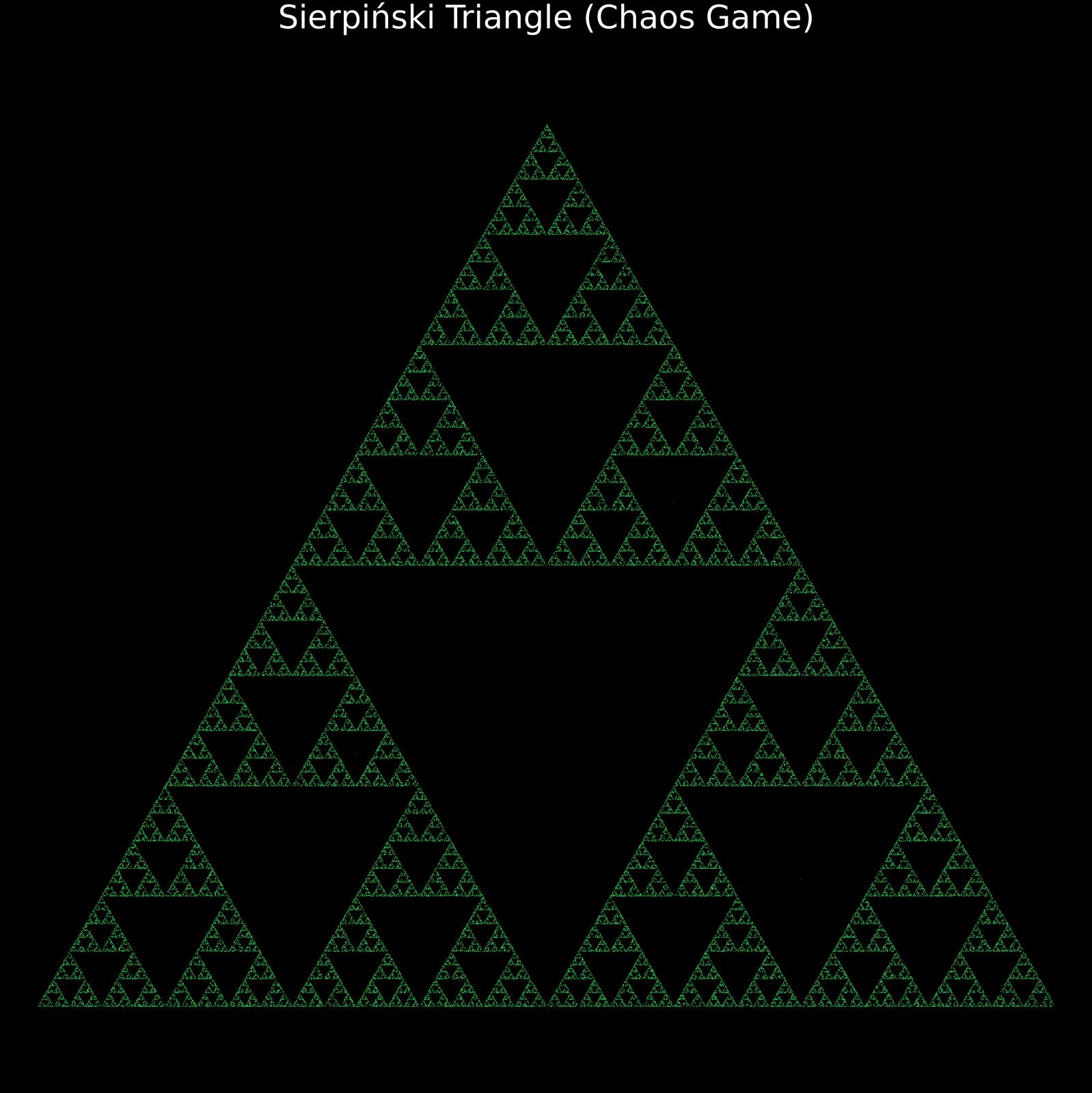

The Sierpinski Triangle

One of the simplest fractals to understand. Start with a solid triangle, remove the middle 1/4th (the upside-down triangle), and repeat for the remaining three triangles forever. It creates a structure with zero area but infinite complexity.

Its fractal dimension is: $$D = \frac{\log 3}{\log 2} \approx 1.585$$ This means it’s more than a line (dimension 1) but less than a filled plane (dimension 2).

Iterated Function Systems (IFS)

What if we could grow a plant from pure mathematics? IFS fractals do exactly that—applying random affine transformations (stretching, rotating, shifting) to build organic-looking structures.

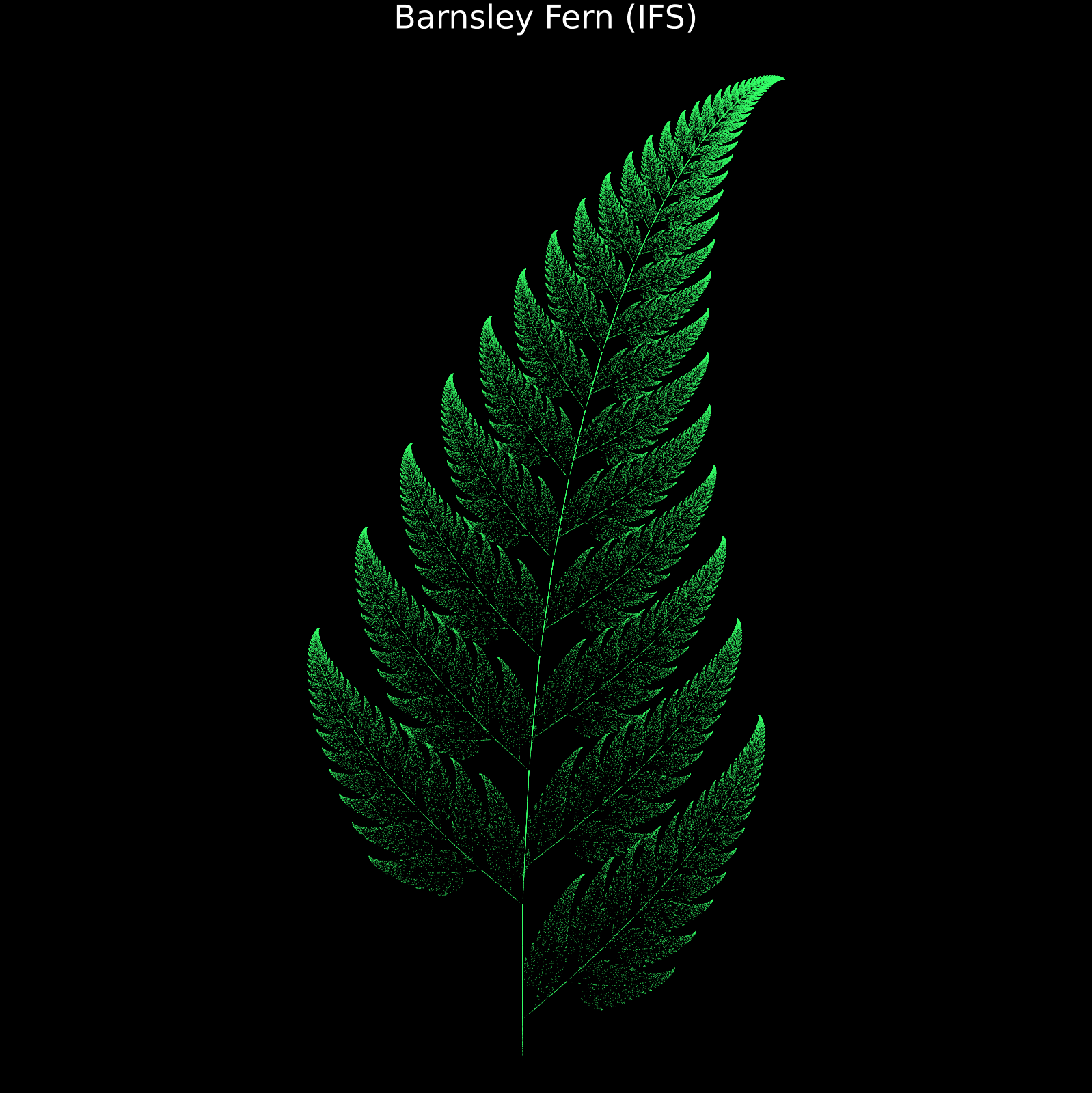

The Barnsley Fern

This fractal mimics a Black Spleenwort fern with uncanny accuracy. It uses four affine transformations applied probabilistically:

$$\begin{pmatrix} x_{n+1} \ y_{n+1} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} a & b \ c & d \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x_n \ y_n \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} e \ f \end{pmatrix}$$

Remarkably, just four sets of coefficients (representing the stem, frond, and two leaflets), applied millions of times at random, build up the image of a perfect, organic-looking fern.

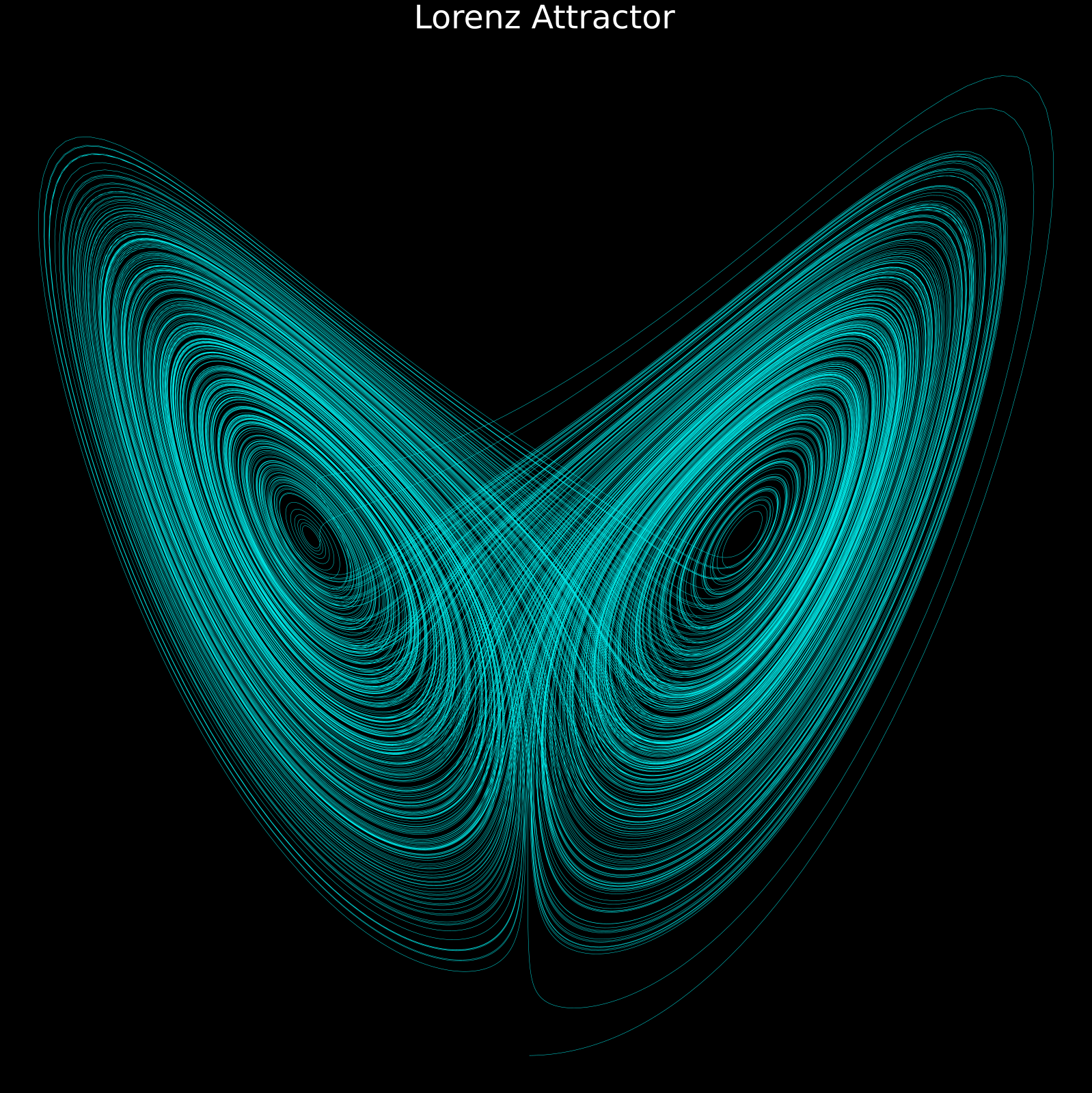

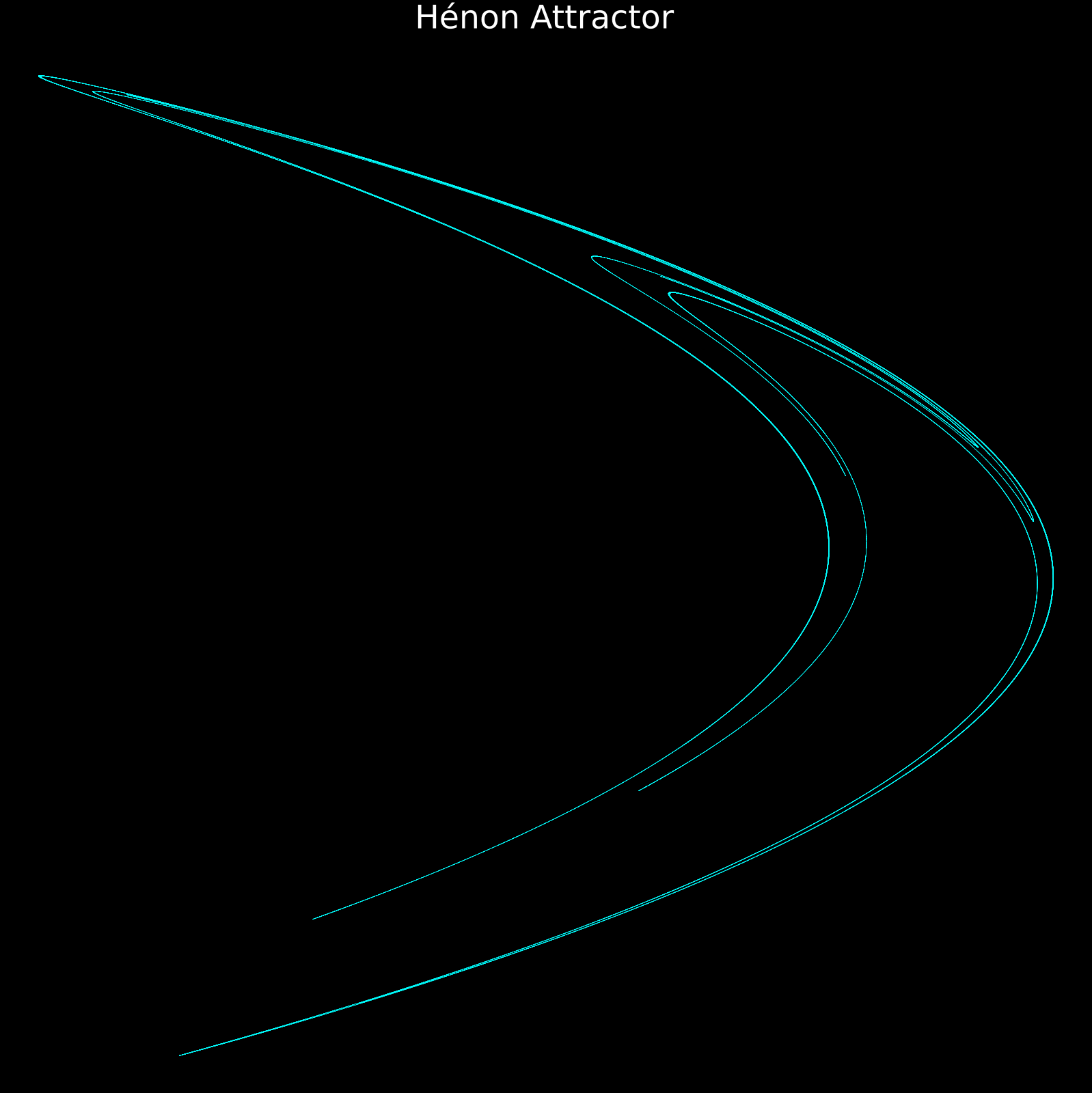

The Chaos of Nature (Strange Attractors)

Now we enter the realm of dynamical systems—equations that describe how things evolve over time. Weather, heartbeats, and planetary orbits all live here. And so do fractals.

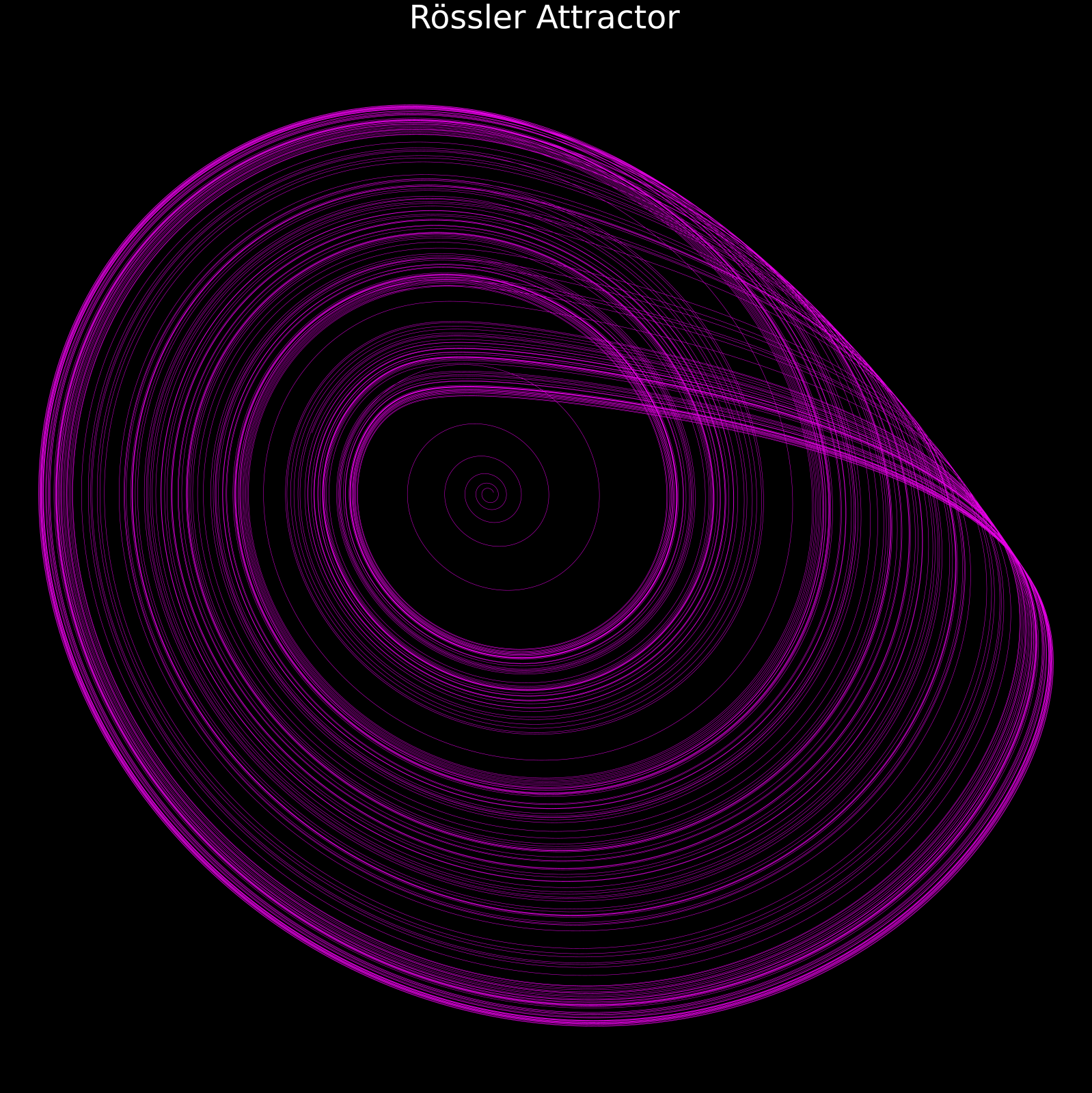

The Rössler Attractor

Discovered by Otto Rössler in 1976, this is a simpler cousin of the Lorenz system but equally chaotic. It is defined by the following system of differential equations:

$$\frac{dx}{dt} = -y - z, \quad \frac{dy}{dt} = x + ay, \quad \frac{dz}{dt} = b + z(x - c)$$

With typical parameters $a = 0.2$, $b = 0.2$, $c = 5.7$, these equations produce a beautiful spiral band that loops in an unpredictable pattern. Like the Lorenz attractor, tiny changes in initial conditions lead to completely different trajectories over time.

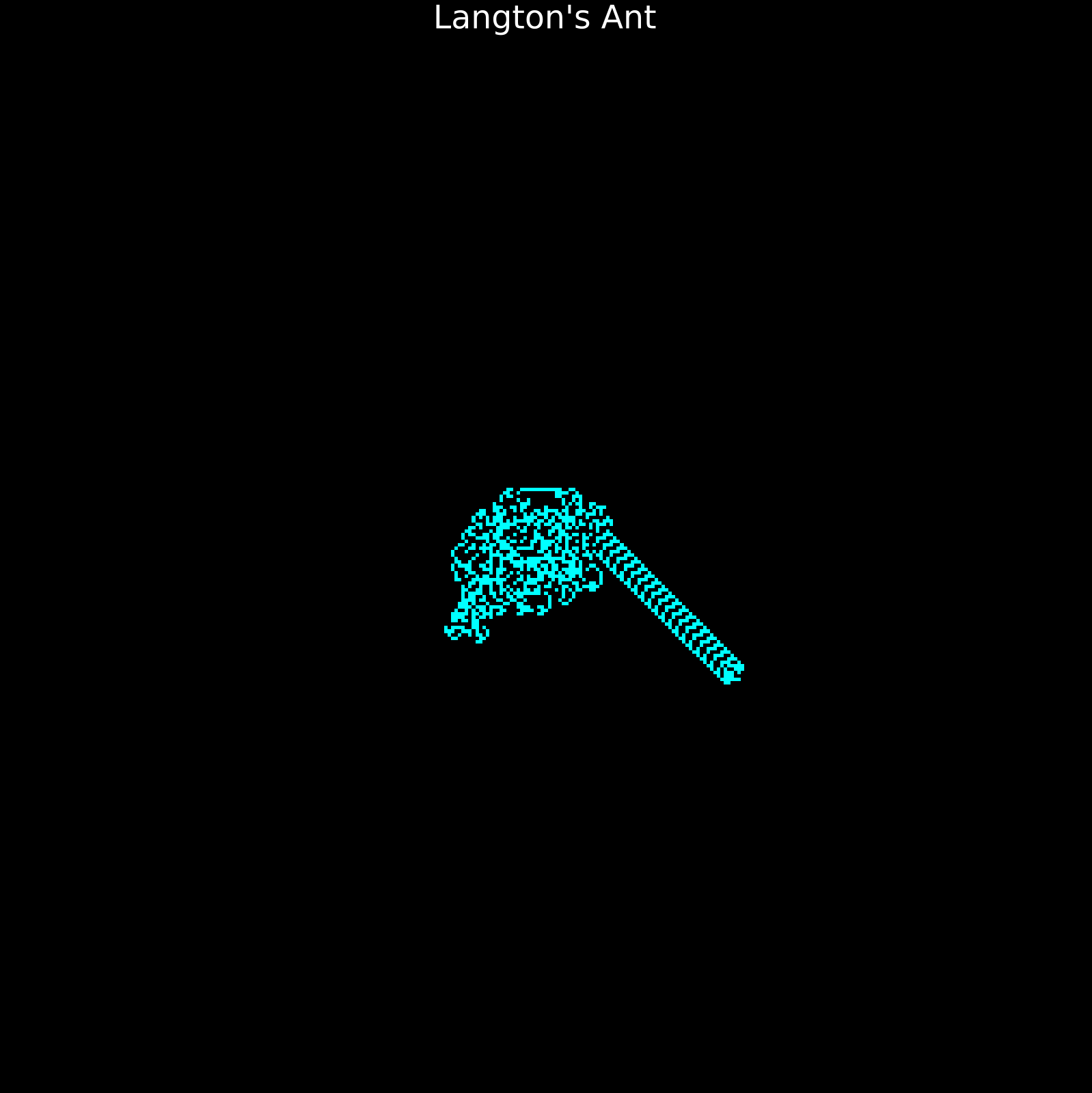

Cellular Automata

Forget equations entirely. What if complexity arose from nothing more than neighbors talking to each other on a grid? Welcome to cellular automata, where the whole truly is greater than the sum of its parts.

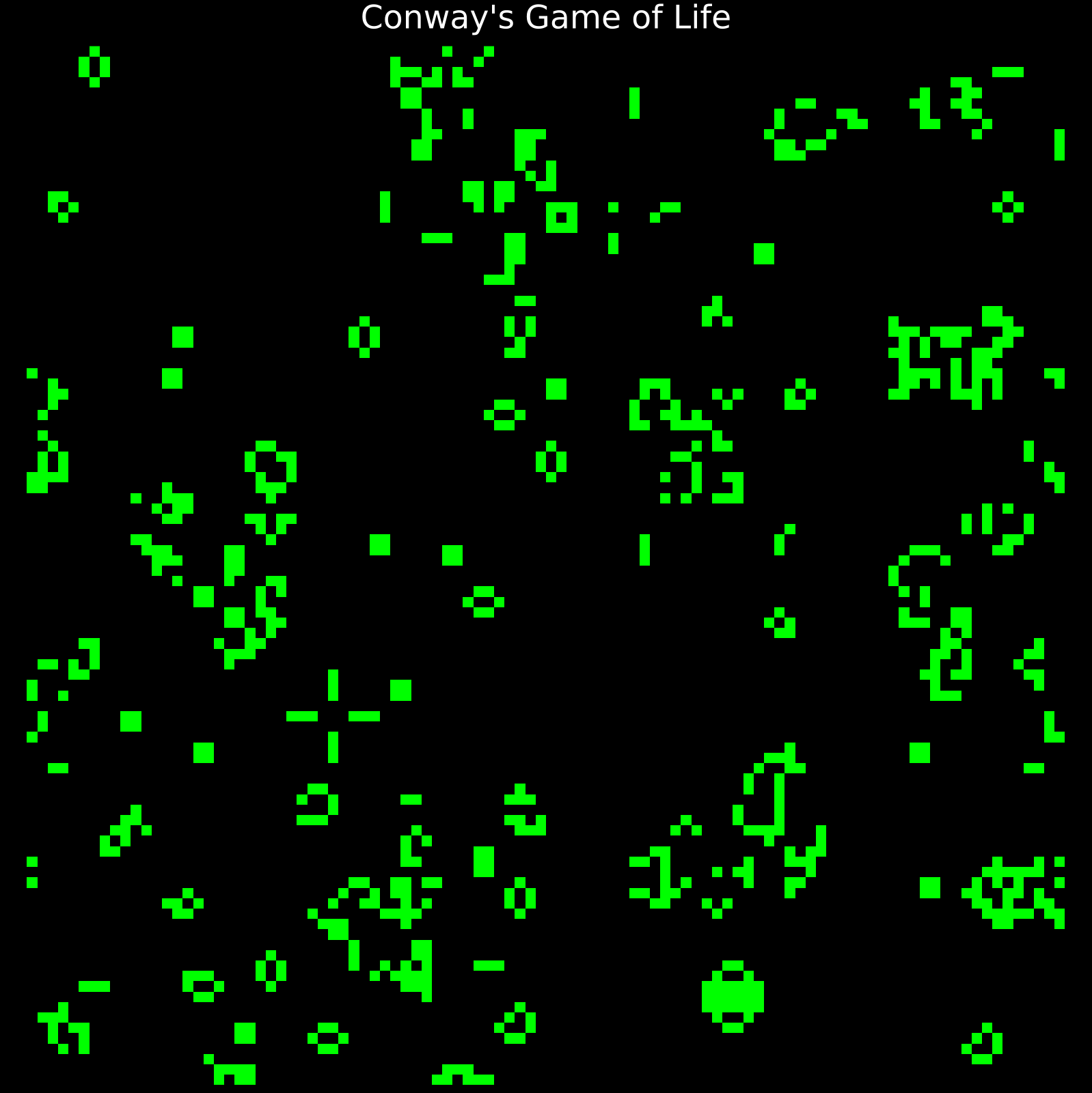

Conway’s Game of Life

A simulation played on a grid where cells live or die based on the number of neighbors. The rules are elegantly simple:

- Birth: A dead cell with exactly 3 neighbors becomes alive

- Survival: A live cell with 2 or 3 neighbors stays alive

- Death: All other live cells die (underpopulation or overpopulation)

From these simple rules, complex “life-forms” like gliders and spaceships emerge, showing how life-like behavior can arise from determinism.

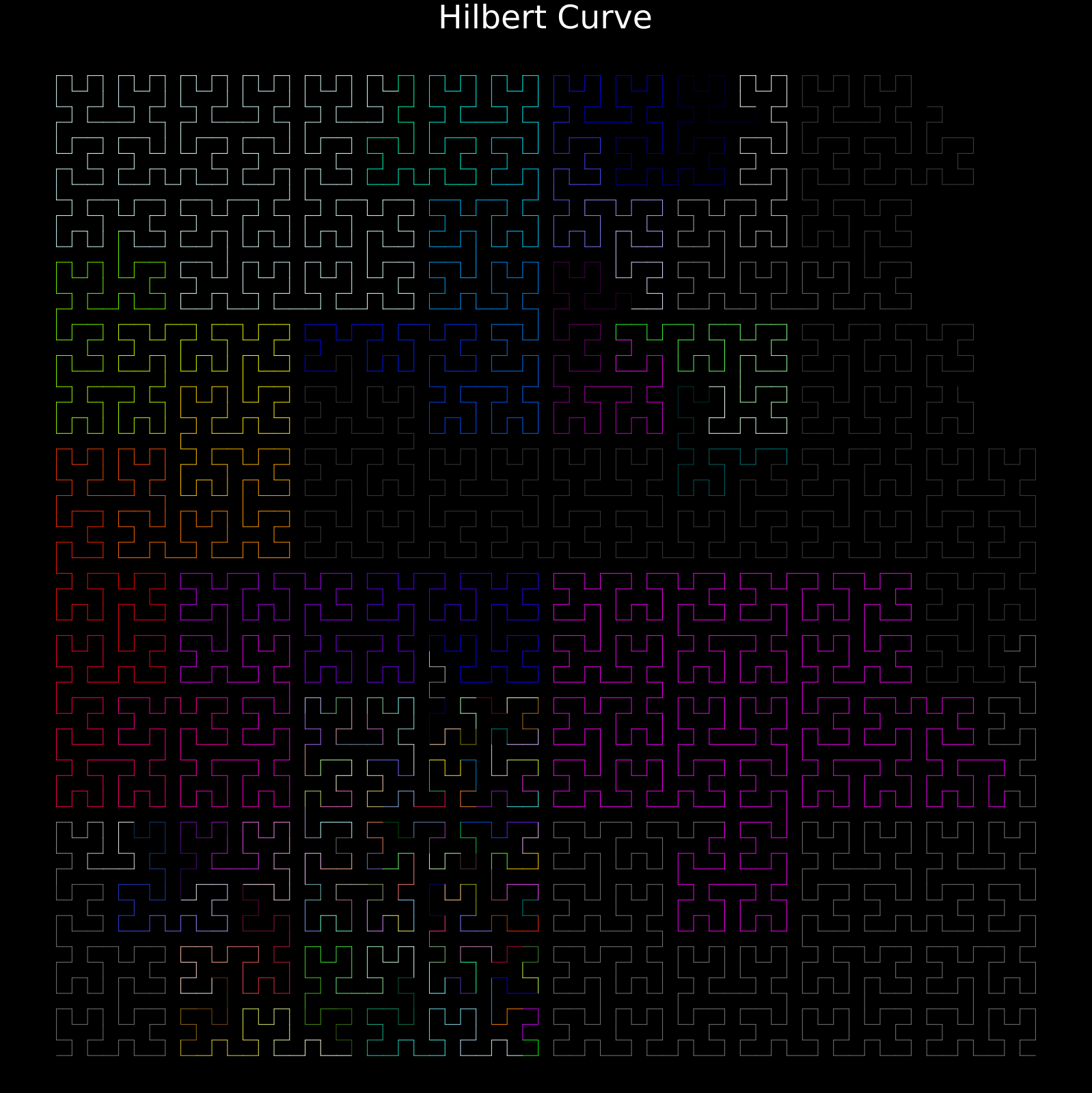

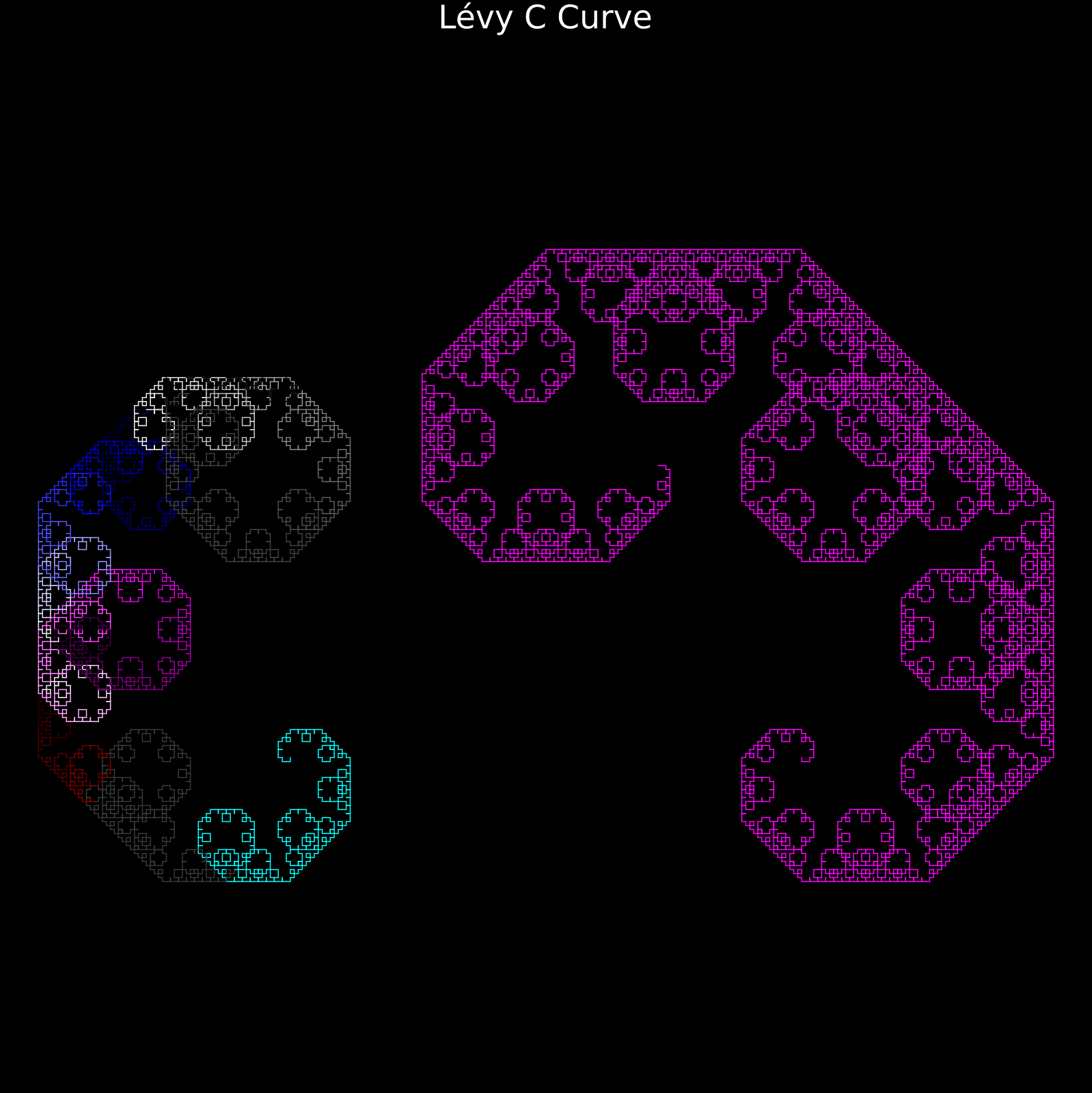

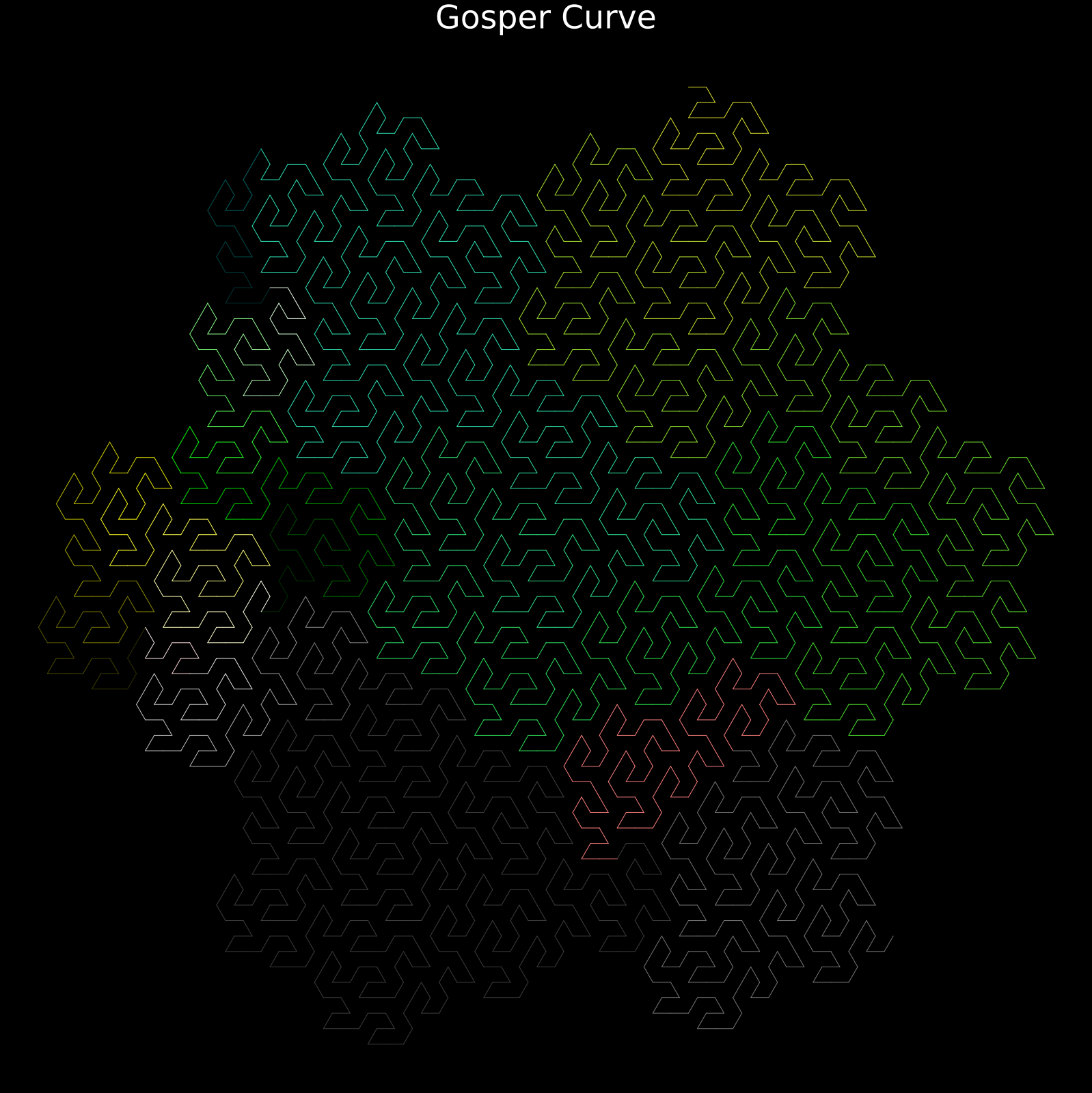

L-System Curves

Botanist Aristid Lindenmayer invented L-Systems to model how plants grow. The secret? String rewriting rules that expand simple instructions into elaborate branching patterns.

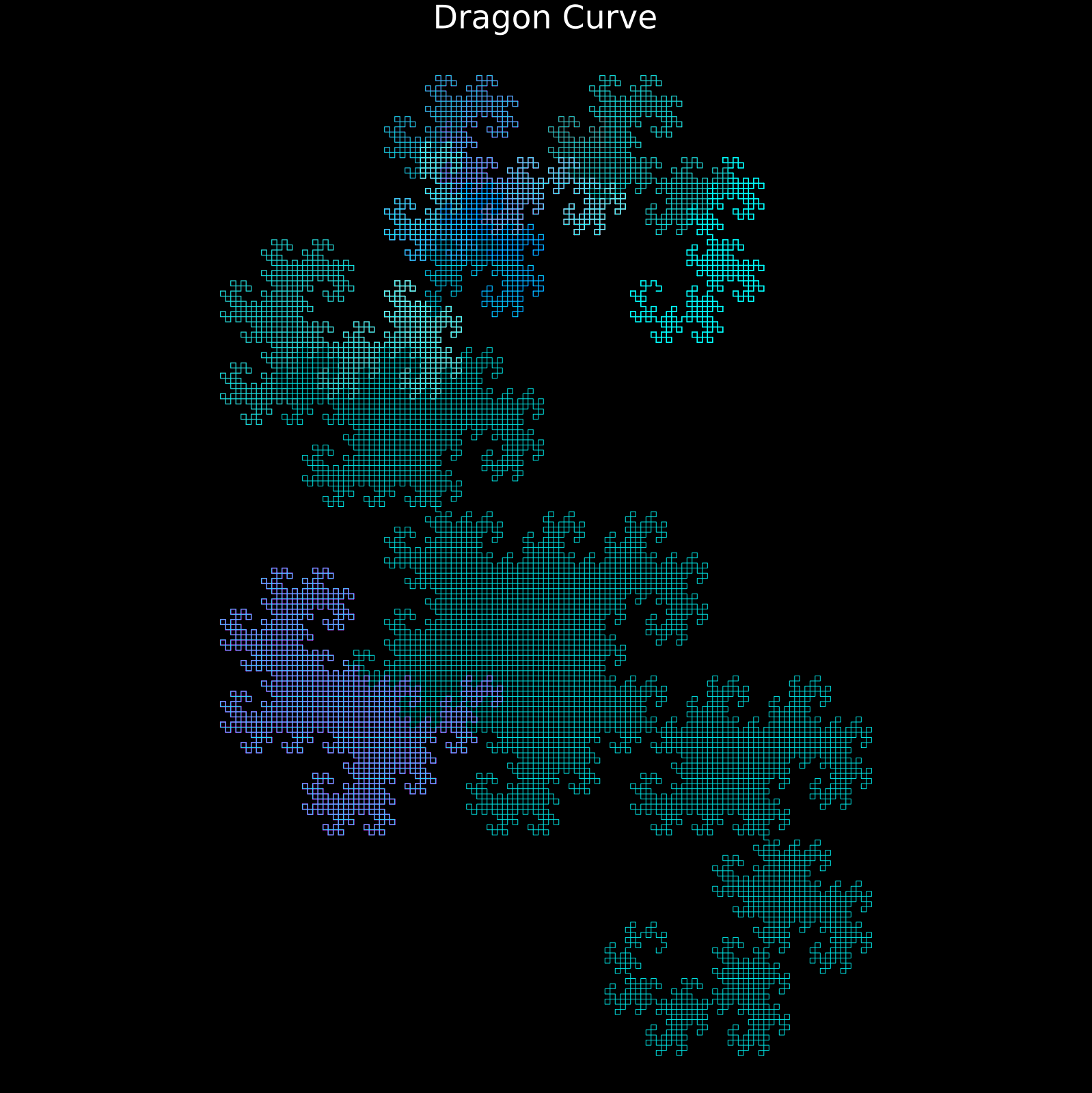

The Dragon Curve

Imagine taking a strip of paper, folding it in half repeatedly, and then unfolding it so each crease is at a 90-degree angle. The L-System rules are:

- Axiom:

FX - Rules:

X → X+YF+,Y → -FX-Y

Where F means “draw forward”, + means “turn right 90°”, and - means “turn left 90°”. This simple process creates the Dragon Curve, a space-filling curve that can fit perfectly together like a jigsaw puzzle.

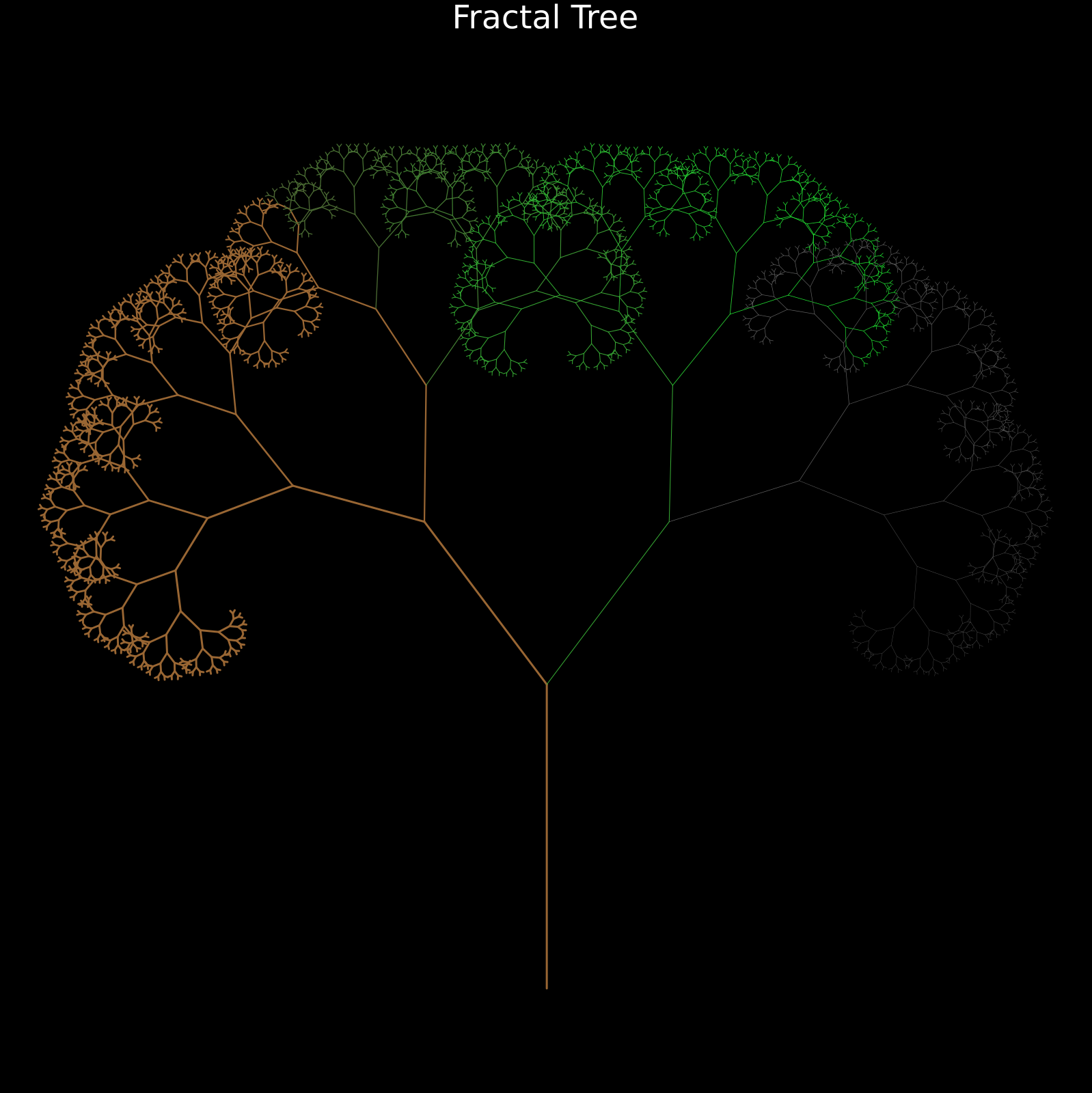

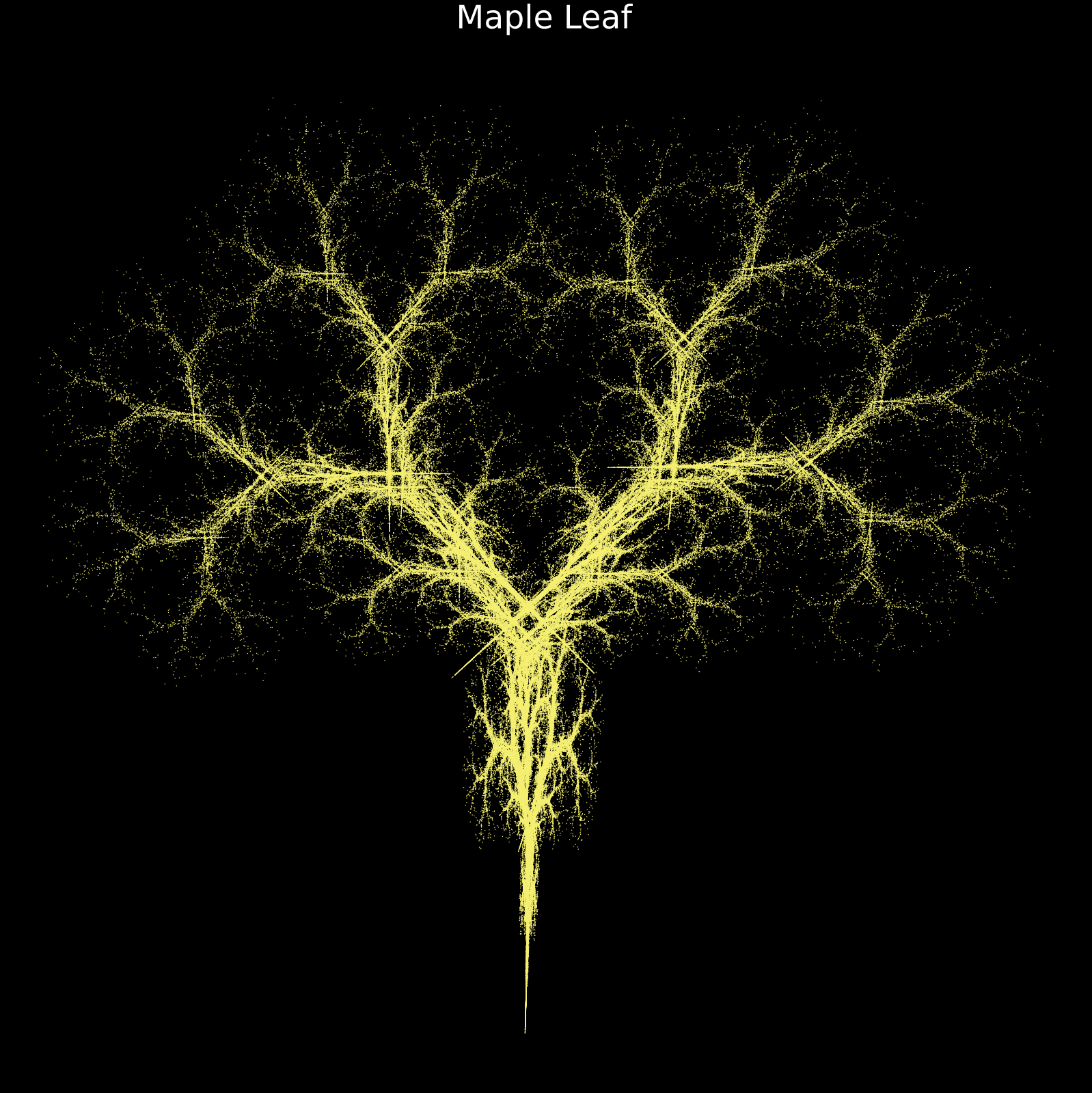

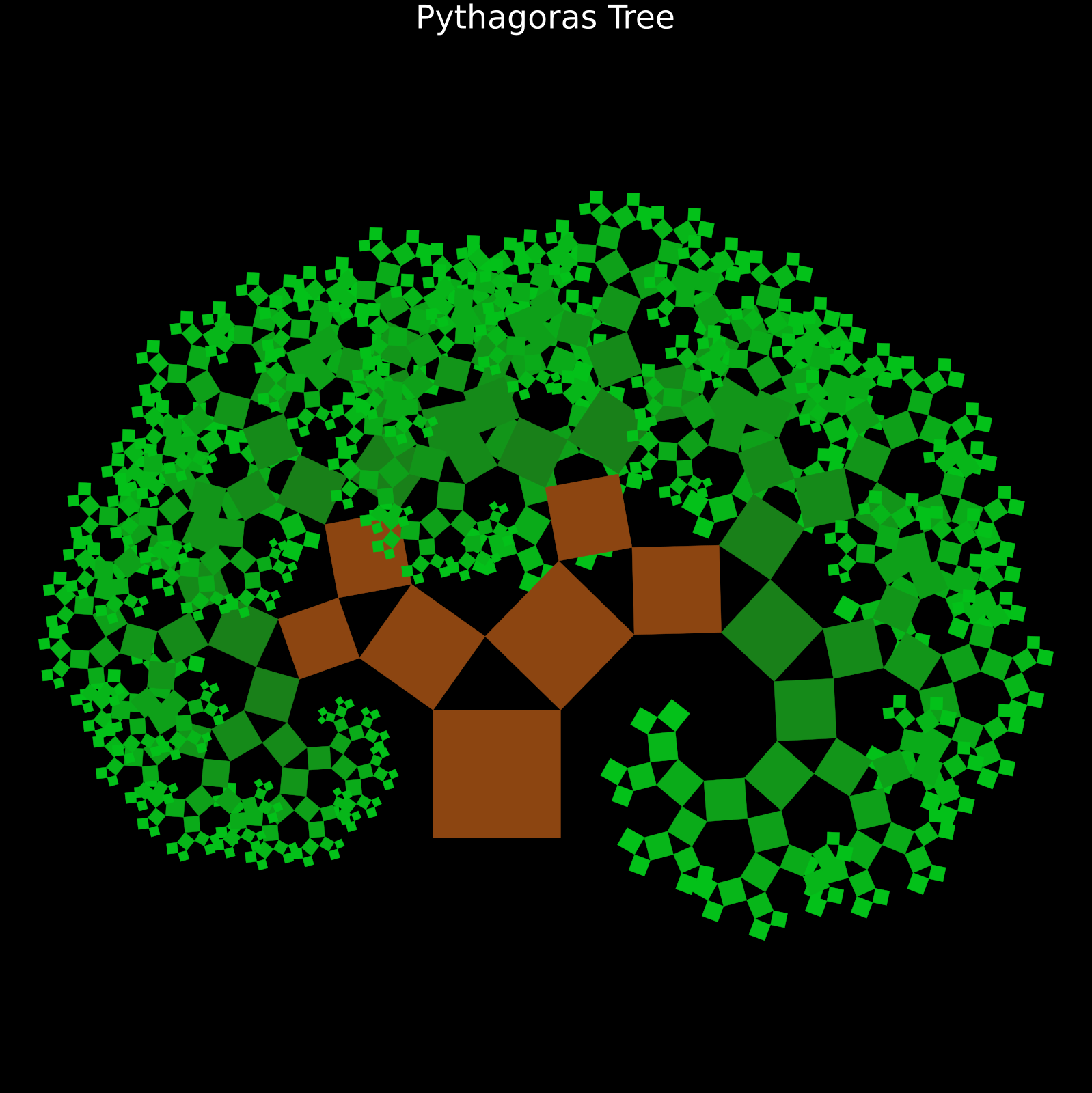

Tree Fractals

Look at any tree, river delta, or network of blood vessels—you’ll see the same branching pattern repeated at every scale. This is no accident; nature loves fractal trees.

The Recursive Fractal Tree

By taking a “trunk” and splitting it into two smaller branches at an angle, then repeating this for every new branch, we can generate realistic tree structures. The recursive formula is:

$$L_{n+1} = r \cdot L_n, \quad \theta_{\text{branch}} = \pm \alpha$$

Where $r$ is the length ratio (typically 0.7) and $\alpha$ is the branching angle (typically 20°-45°). Changing these parameters creates entirely different species of “trees.”

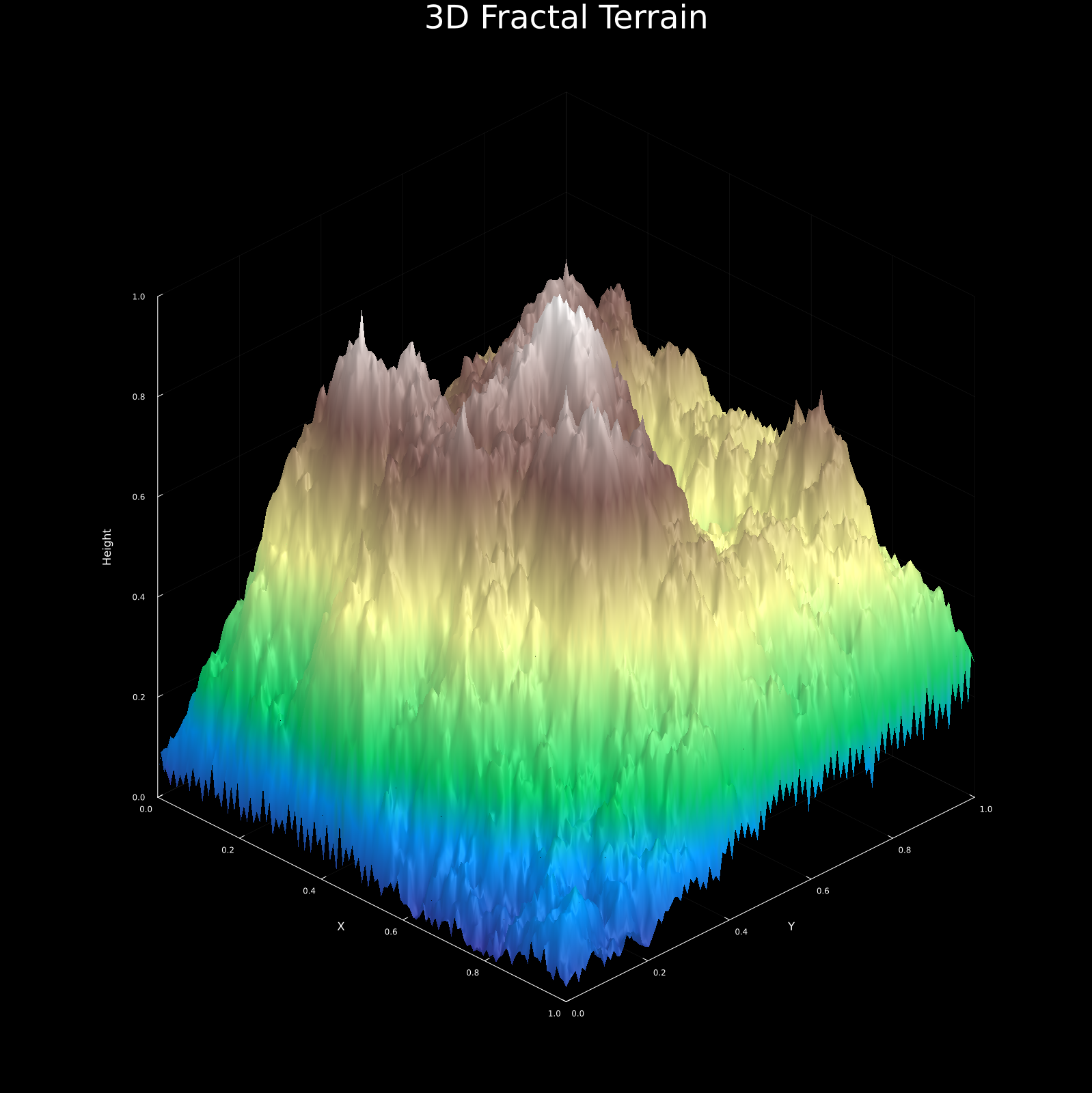

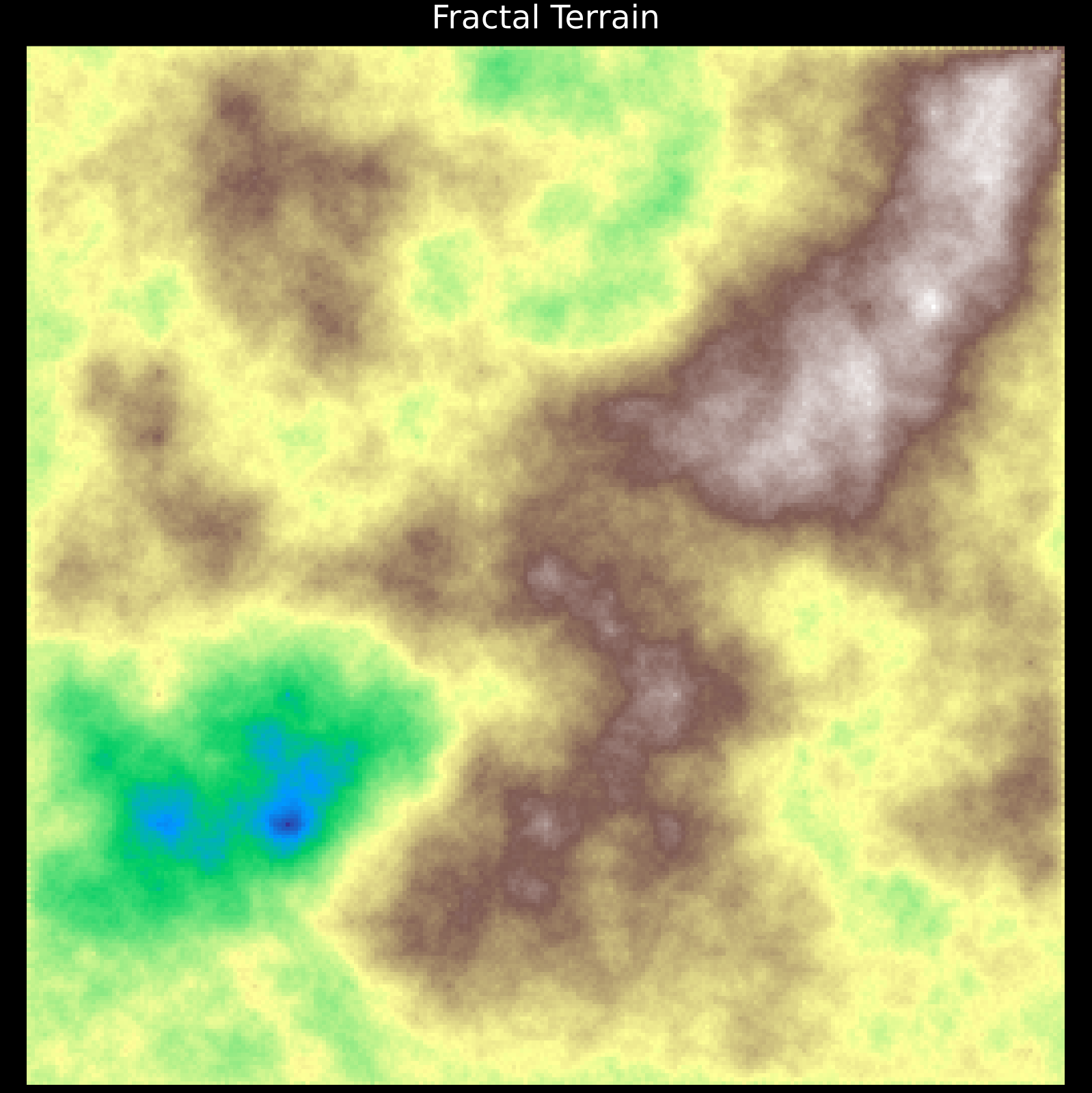

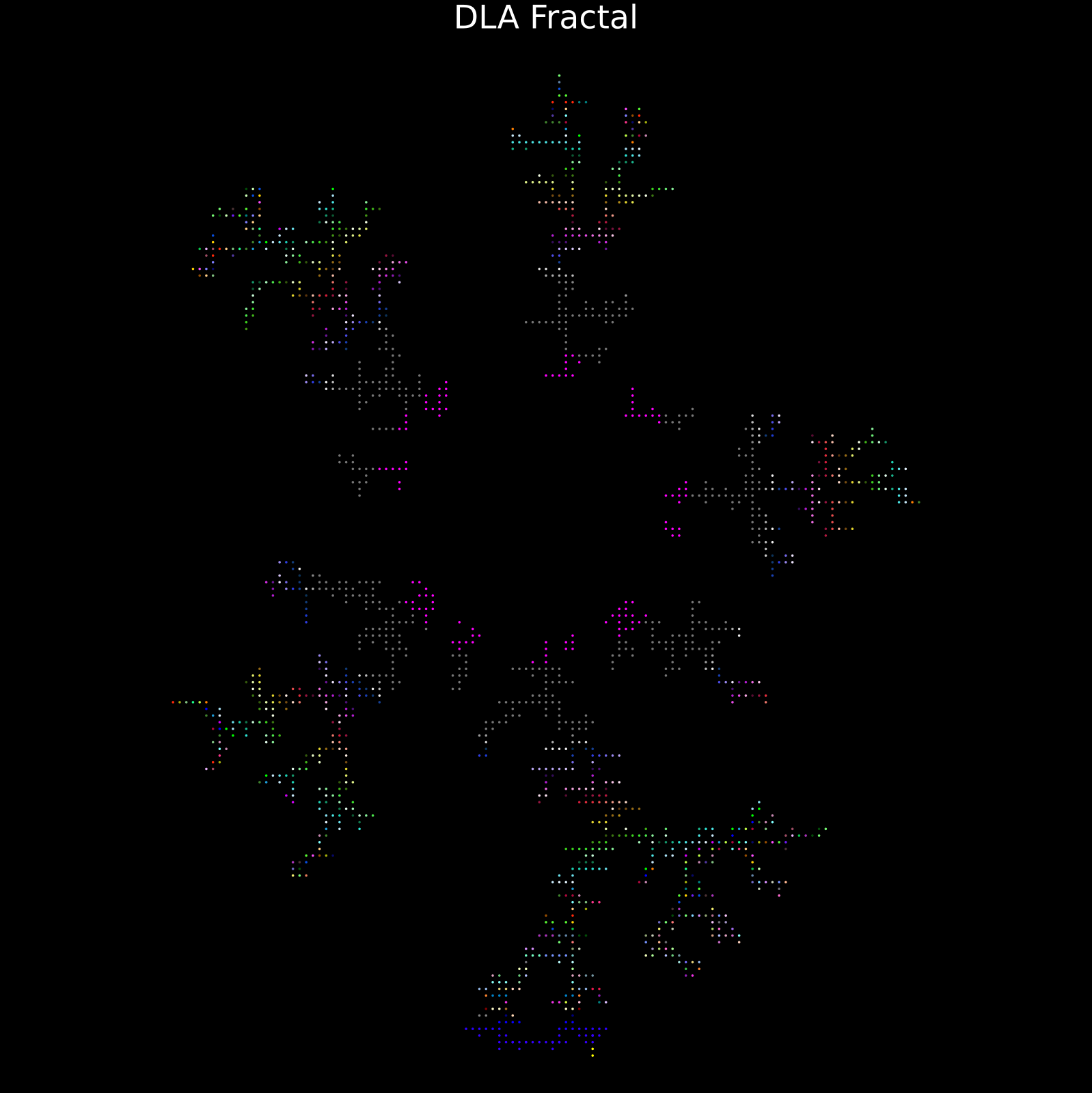

Random Fractals

Perfect symmetry is rare in nature. Mountains aren’t pyramids; clouds aren’t spheres. Random fractals embrace this messiness, injecting controlled noise to create realistic textures.

Fractal Terrain

Using algorithms like the “Diamond-Square,” we can generate realistic 3D mountainous landscapes. The key formula for midpoint displacement is:

$$h_{\text{mid}} = \frac{h_1 + h_2}{2} + \text{random}(-d, d), \quad d_{n+1} = d_n \cdot 2^{-H}$$

Where $H$ is the Hurst exponent (roughness), typically 0.5-1.0. By recursively applying this with decreasing displacement $d$, we mimic the erosion and geological processes that form real mountains.

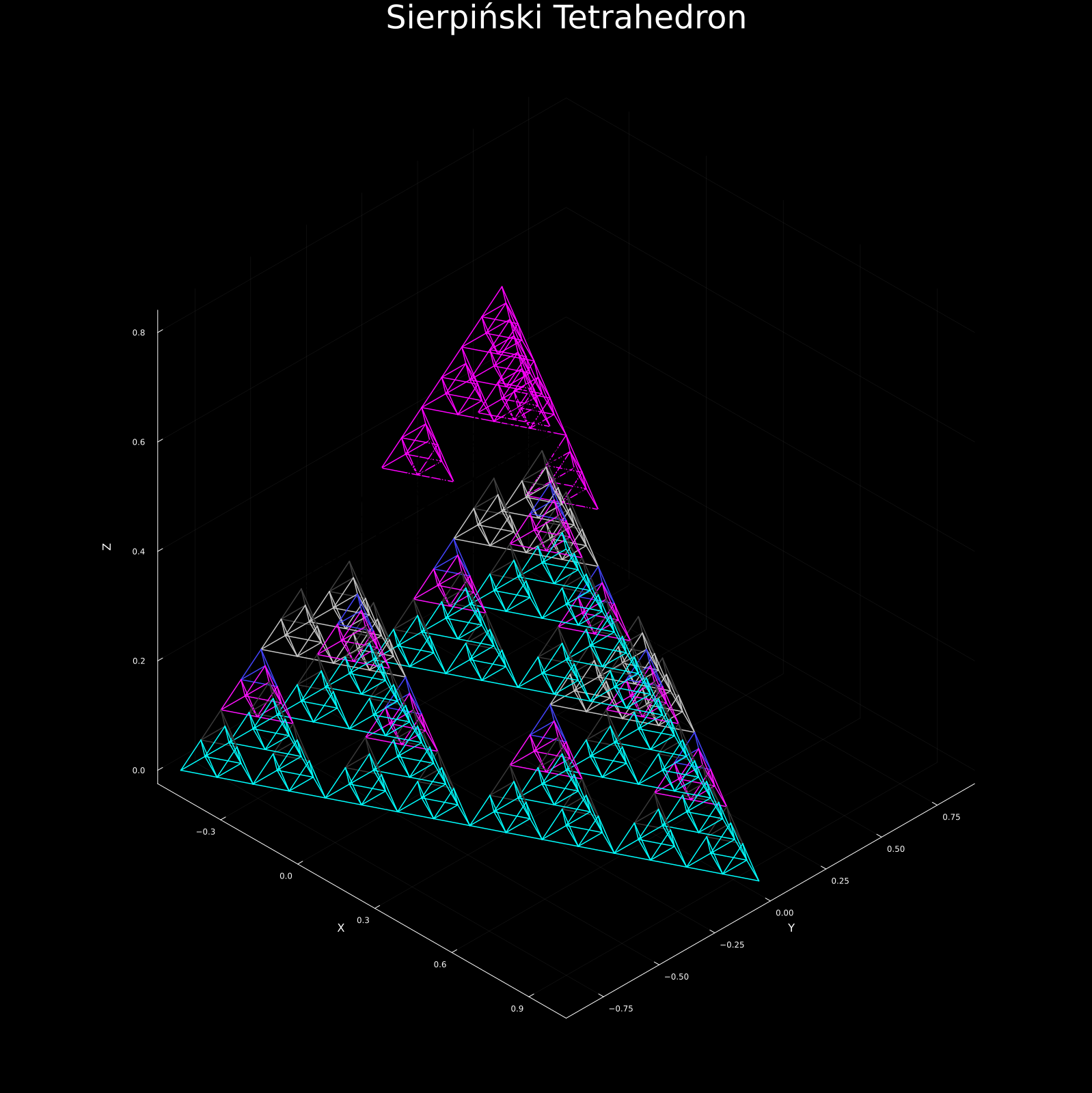

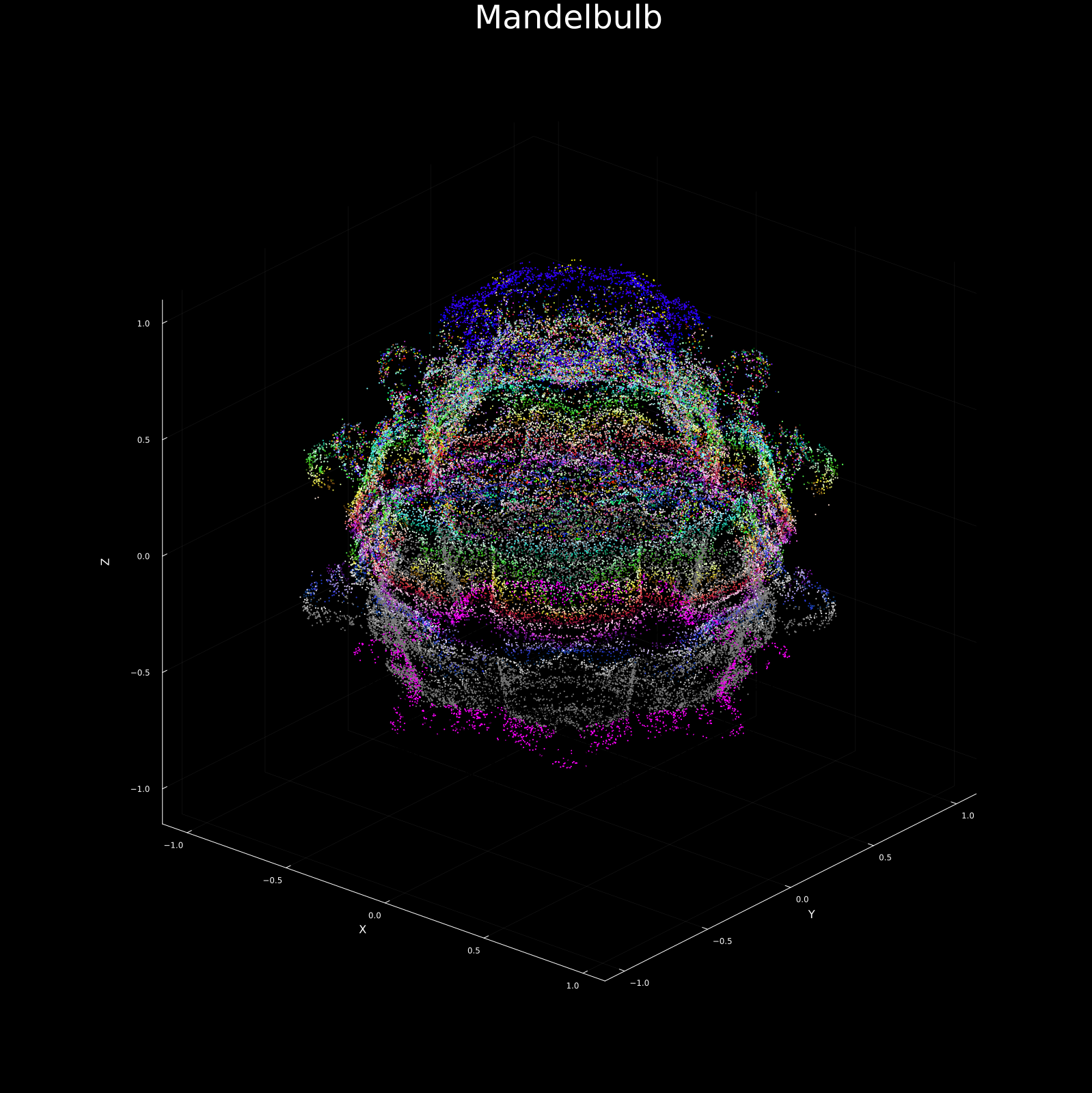

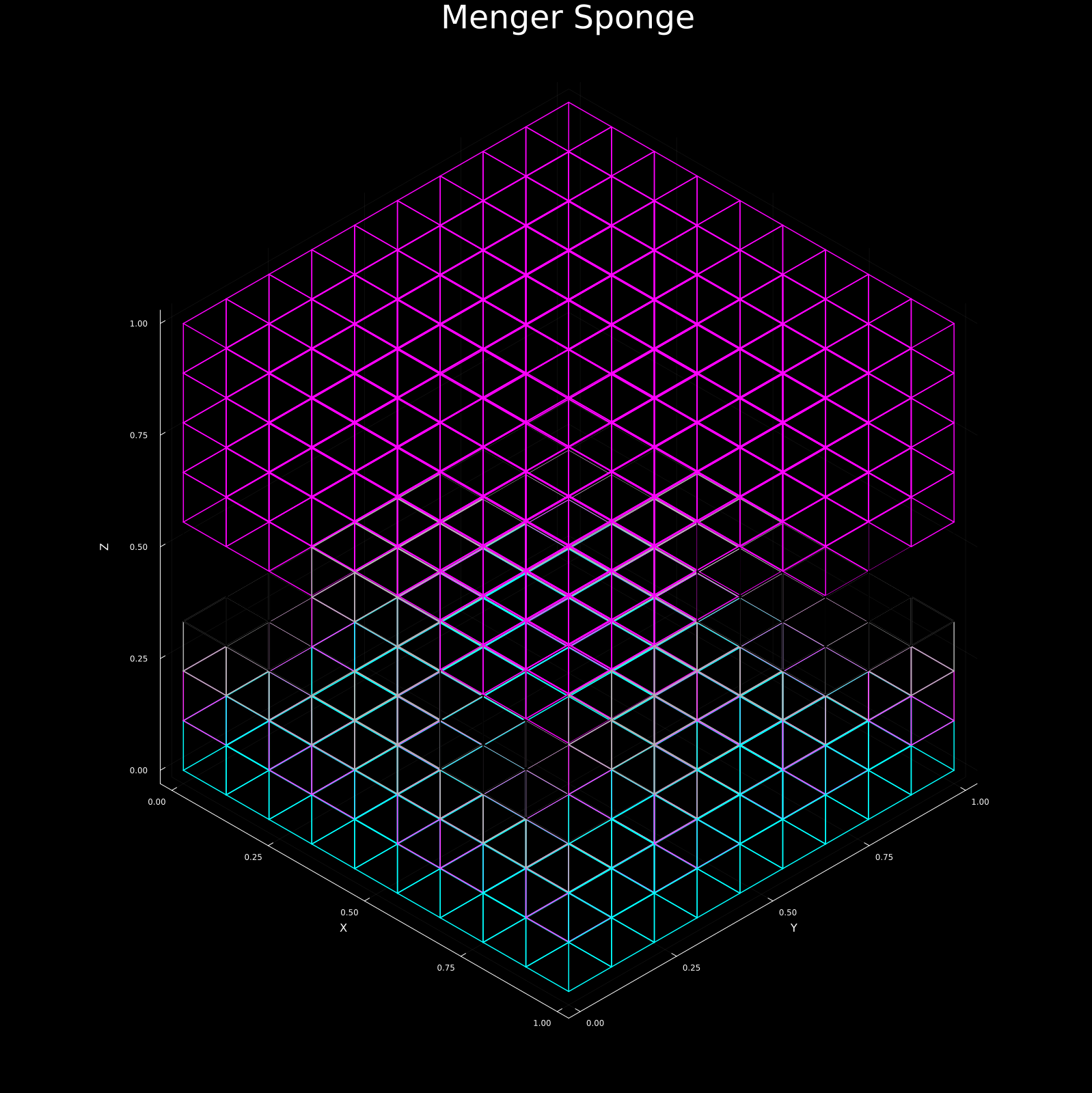

3D Fractals

Finally, we break free from the flat page. Three-dimensional fractals create structures of staggering internal complexity—infinite surface area packed into finite volumes.

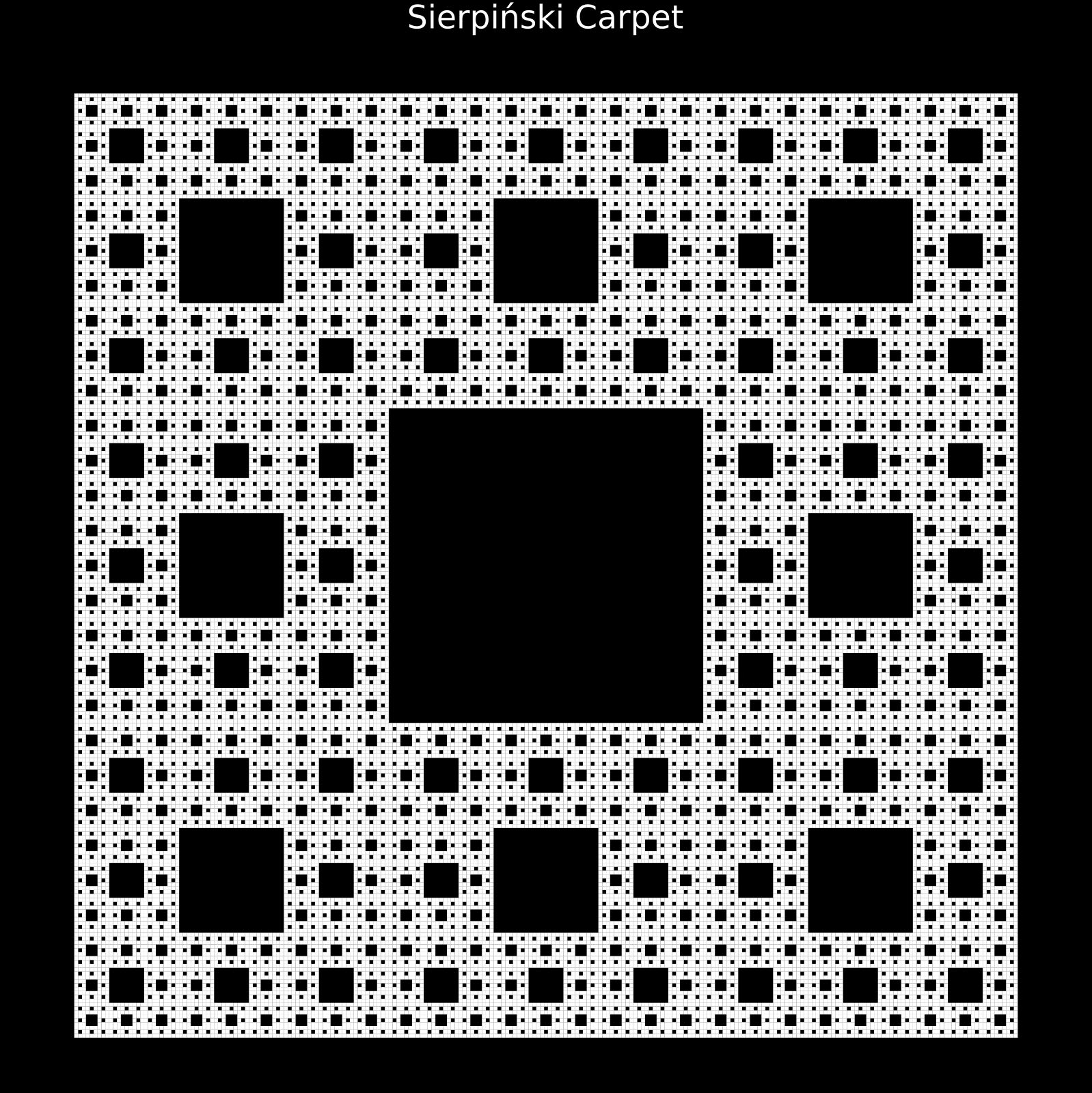

The Menger Sponge

This is the 3D cousin of the Sierpinski Carpet. Start with a cube, divide it into 27 smaller cubes, and remove the center cube plus the center cubes of the 6 faces (7 cubes total, leaving 20). Repeat this forever.

Its fractal dimension is: $$D = \frac{\log 20}{\log 3} \approx 2.727$$

You end up with an object that has infinite surface area but zero volume!

Conclusion

Fractals challenge our intuition. They tell us that you don’t need complicated blueprints to build a complicated world. A simple rule, repeated enough times, can create the coastline of a continent, the branching of a tree, or the infinite intricate beauty of the Mandelbrot set.

Fractals in the Real World

Beyond their mathematical beauty, fractals have found practical applications across many fields:

- Computer Graphics & CGI: Fractal algorithms generate realistic mountains, clouds, and forests in movies and video games

- Antenna Design: Fractal antennas can receive multiple frequencies in a compact form factor

- Medical Imaging: Fractal analysis helps detect irregularities in heartbeat rhythms and tumor growth patterns

- Financial Markets: The “roughness” of stock price movements exhibits fractal characteristics

- Data Compression: Fractal image compression exploits self-similarity to achieve high compression ratios

A Philosophical Note

Perhaps the most profound lesson of fractals is this: complexity does not require complicated origins. The universe seems to prefer elegant, recursive rules that unfold into rich tapestries of form and behavior.

Mathematics is often seen as cold and rigid, but in the world of fractals, we see its organic, artistic, and infinite heart.

Further Reading

Books

- Chaos: Making a New Science by James Gleick — The classic introduction to chaos theory and fractals

- The Fractal Geometry of Nature by Benoît Mandelbrot — The foundational work by the father of fractals

- Fractals Everywhere by Michael Barnsley — A more mathematical treatment with IFS theory

Online Resources

- Fractal Foundation — Educational resources and fractal art

- Paul Bourke’s Encyclopaedia — Extensive collection of fractal algorithms

- 3Blue1Brown: Fractals — Visual explanations of mathematical concepts

Interactive Tools

- Mandelbrot Set Explorer — Zoom infinitely into the Mandelbrot Set

- L-System Generator — Create your own L-System fractals

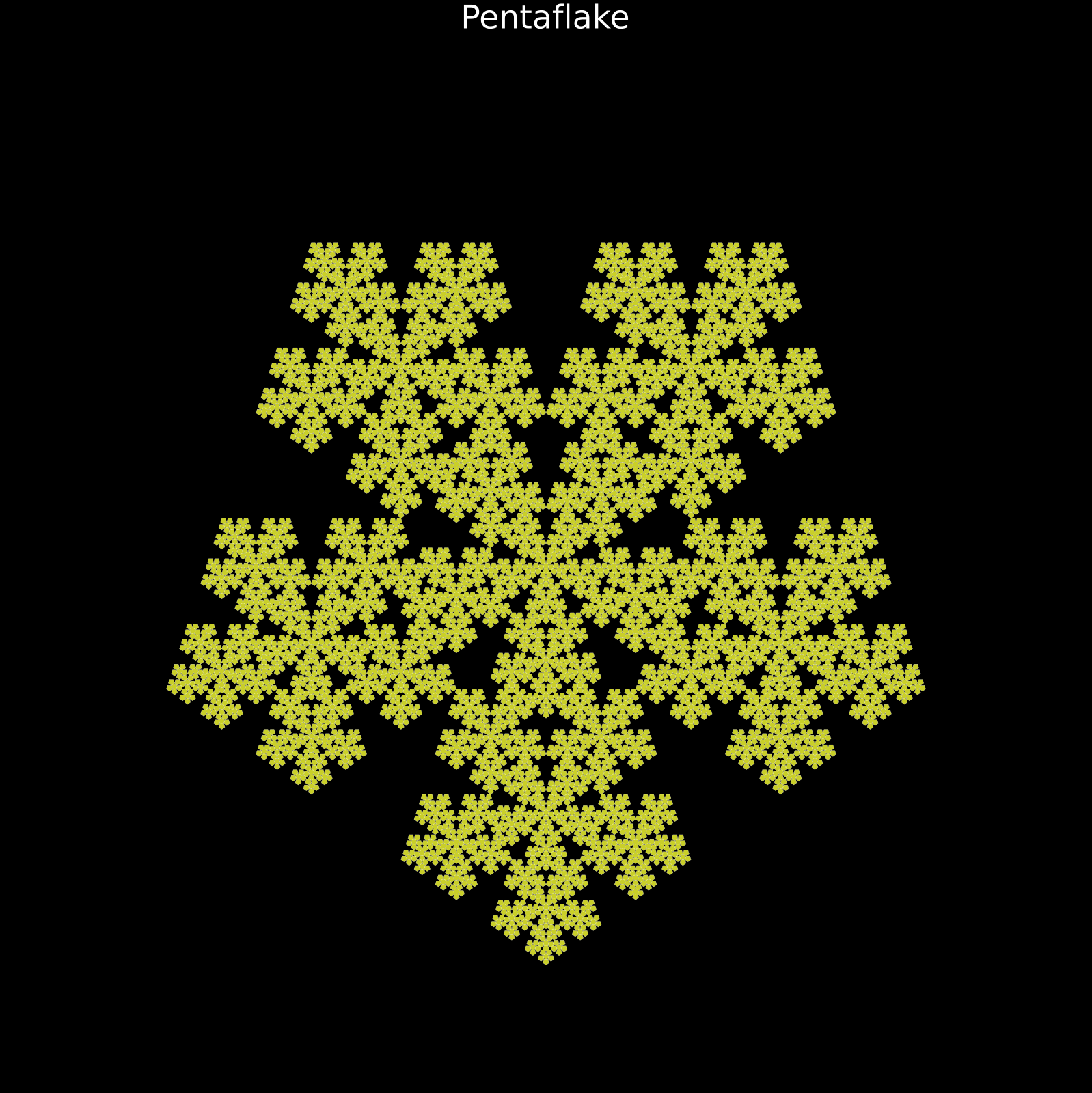

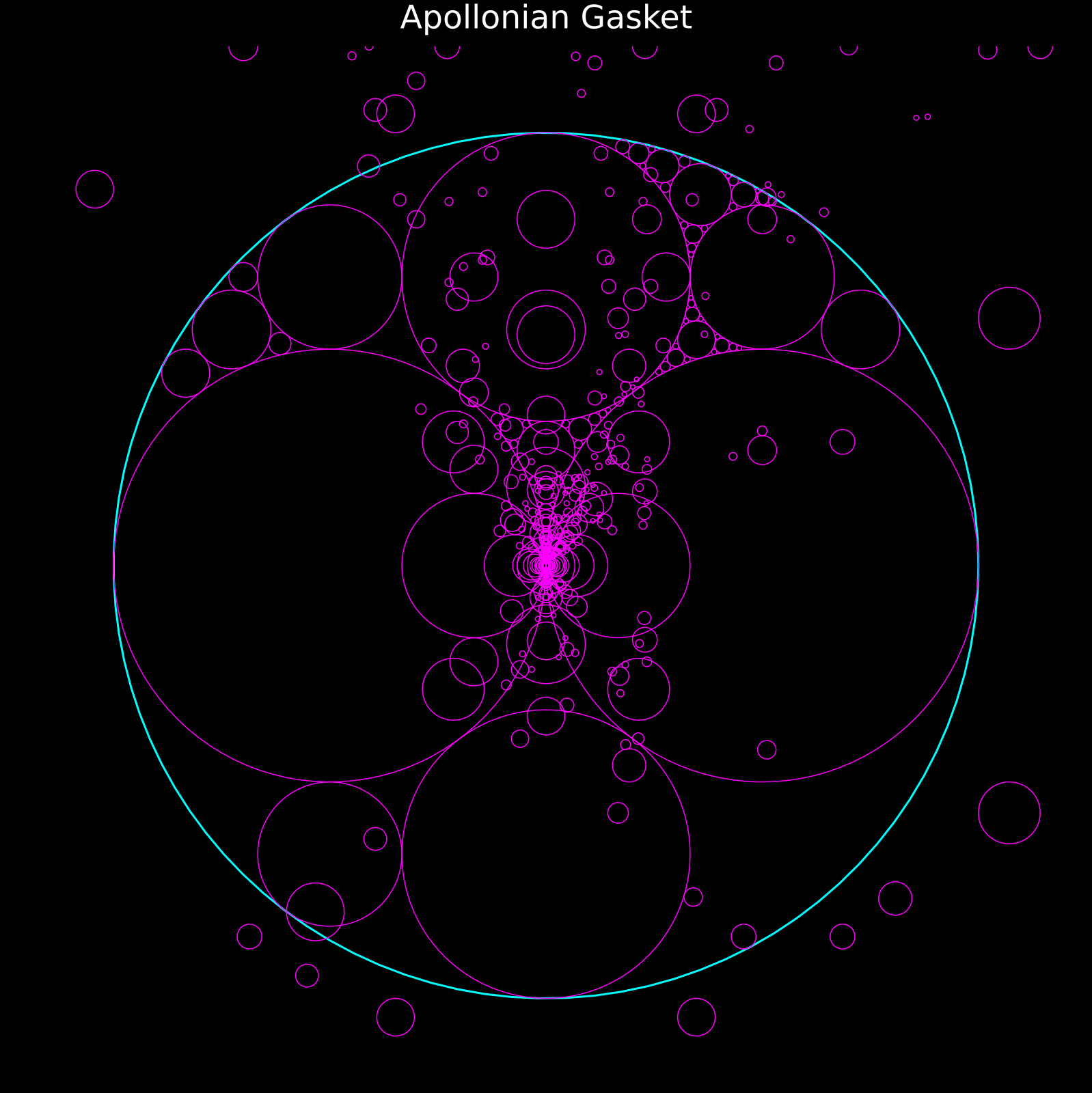

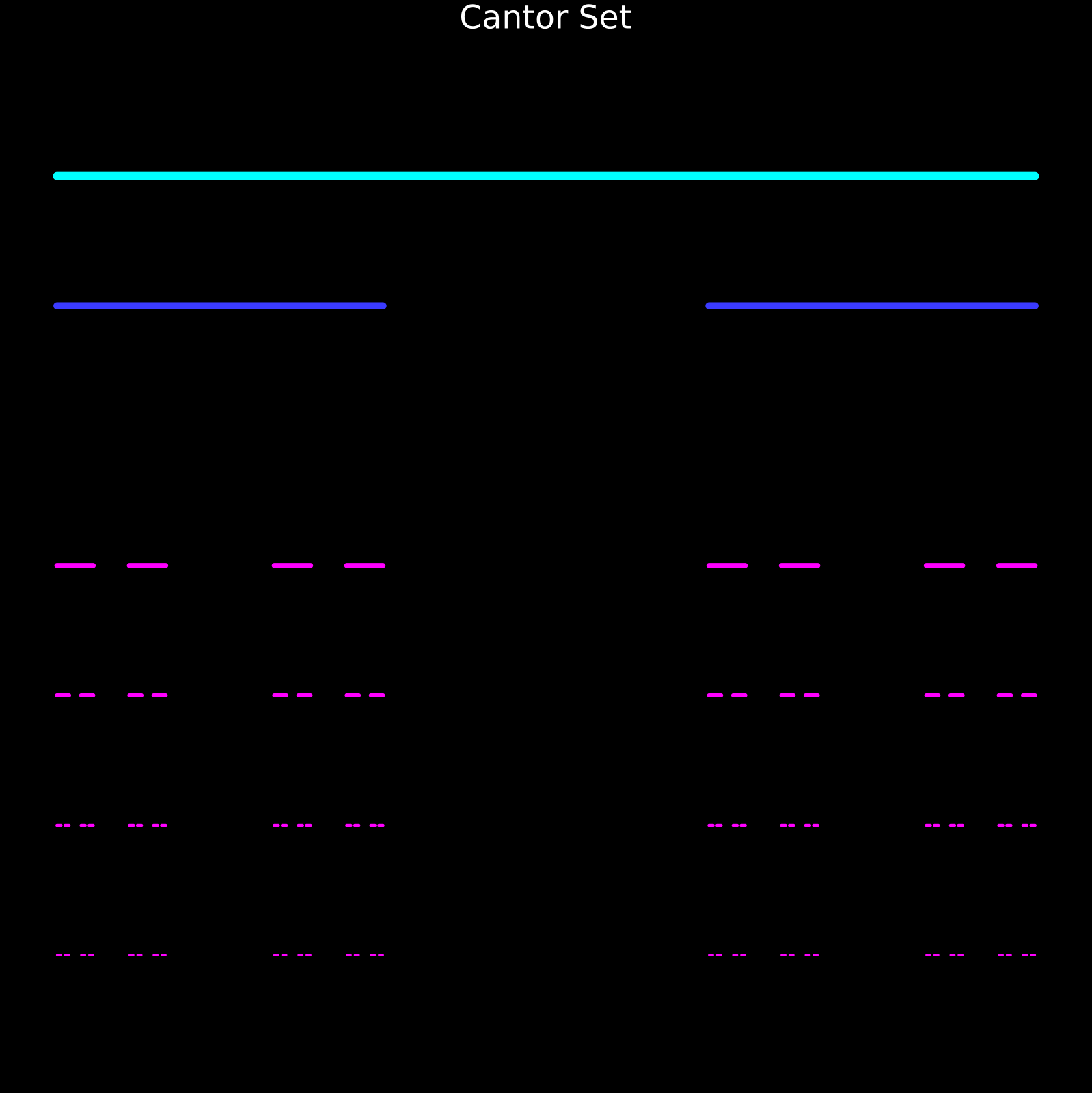

Appendix: The Complete Gallery

We explored 34 different fractals. Below are the ones not featured in the main article, categorized by their family.

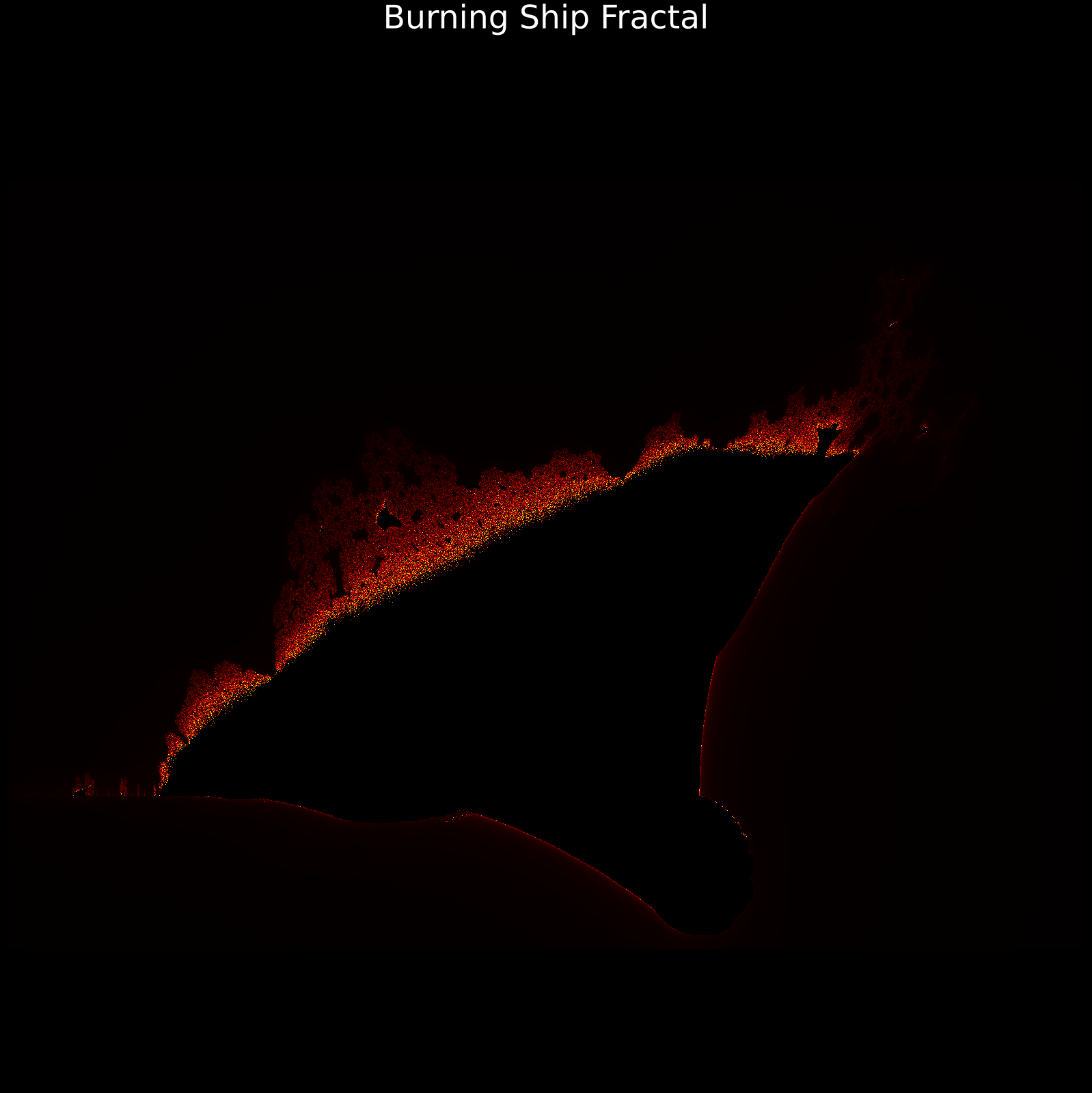

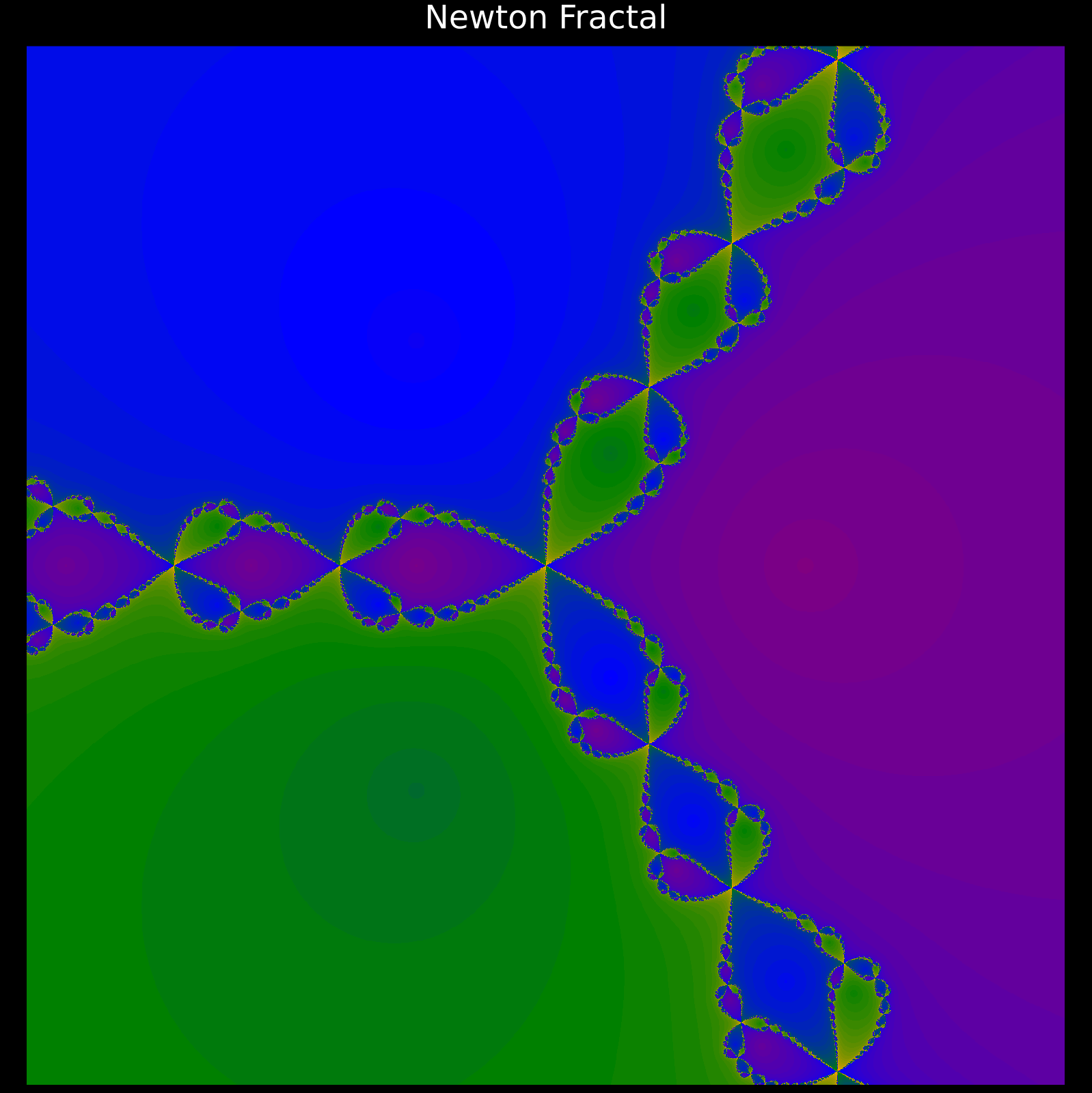

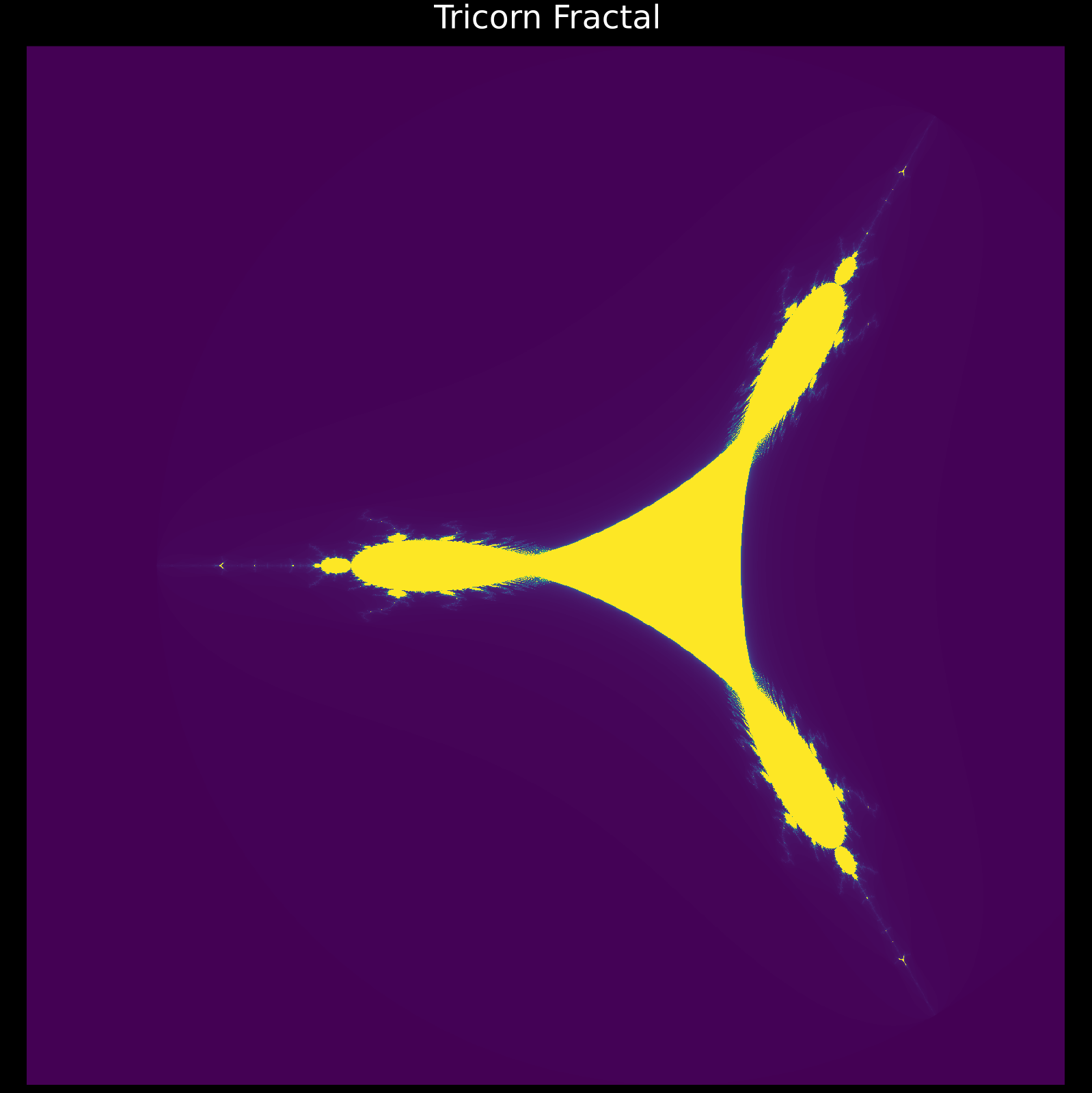

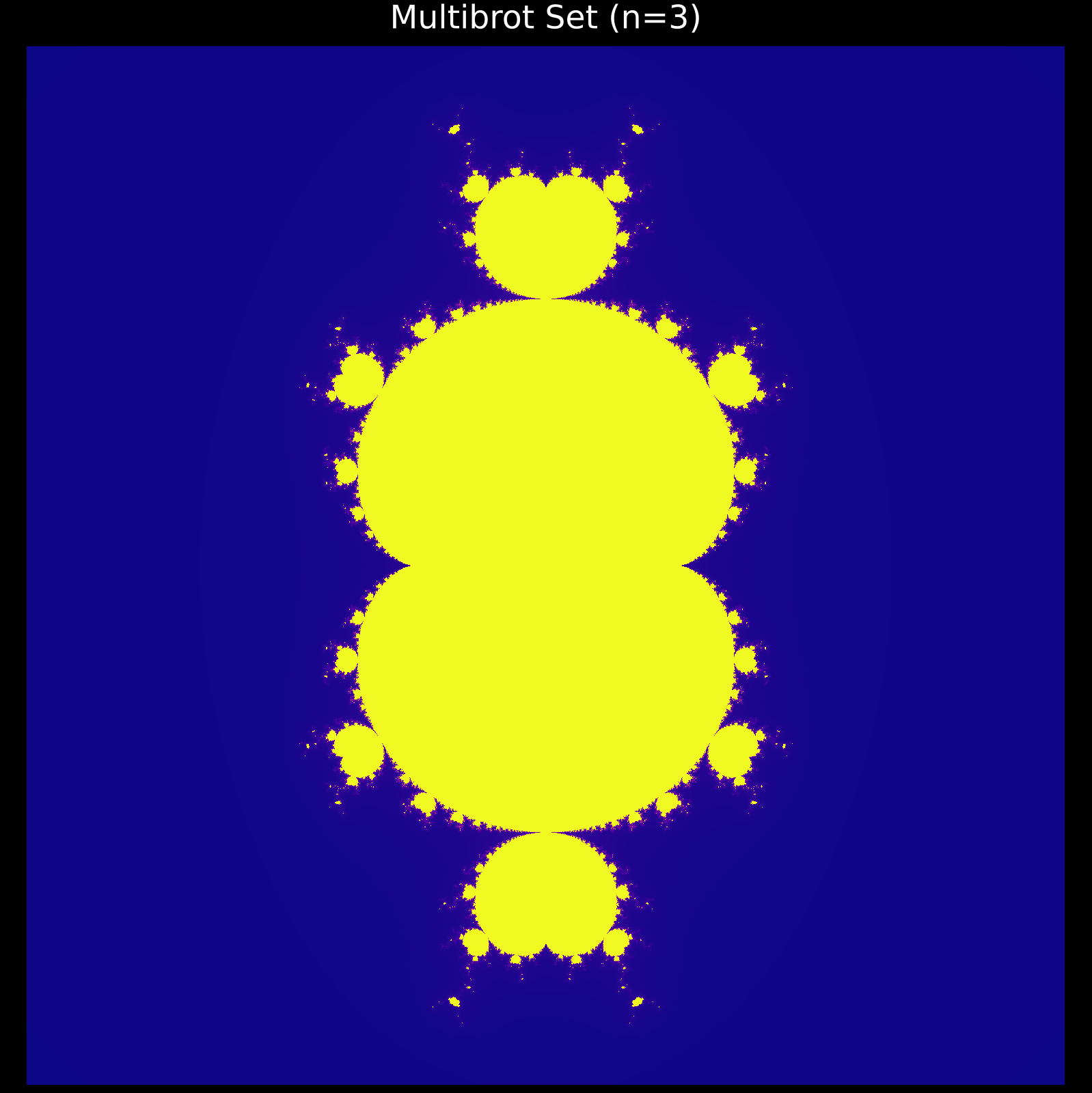

Complex Iteration

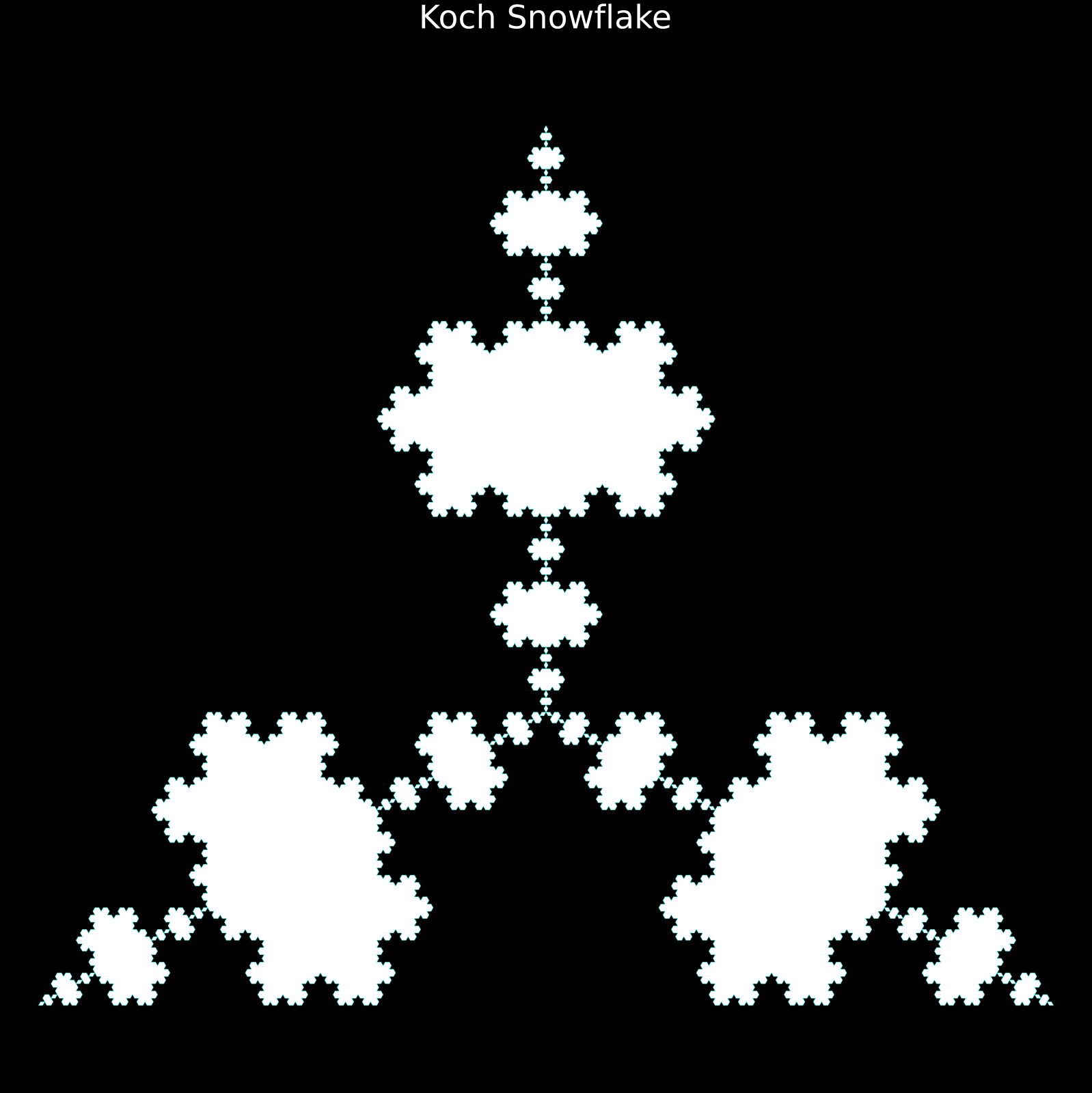

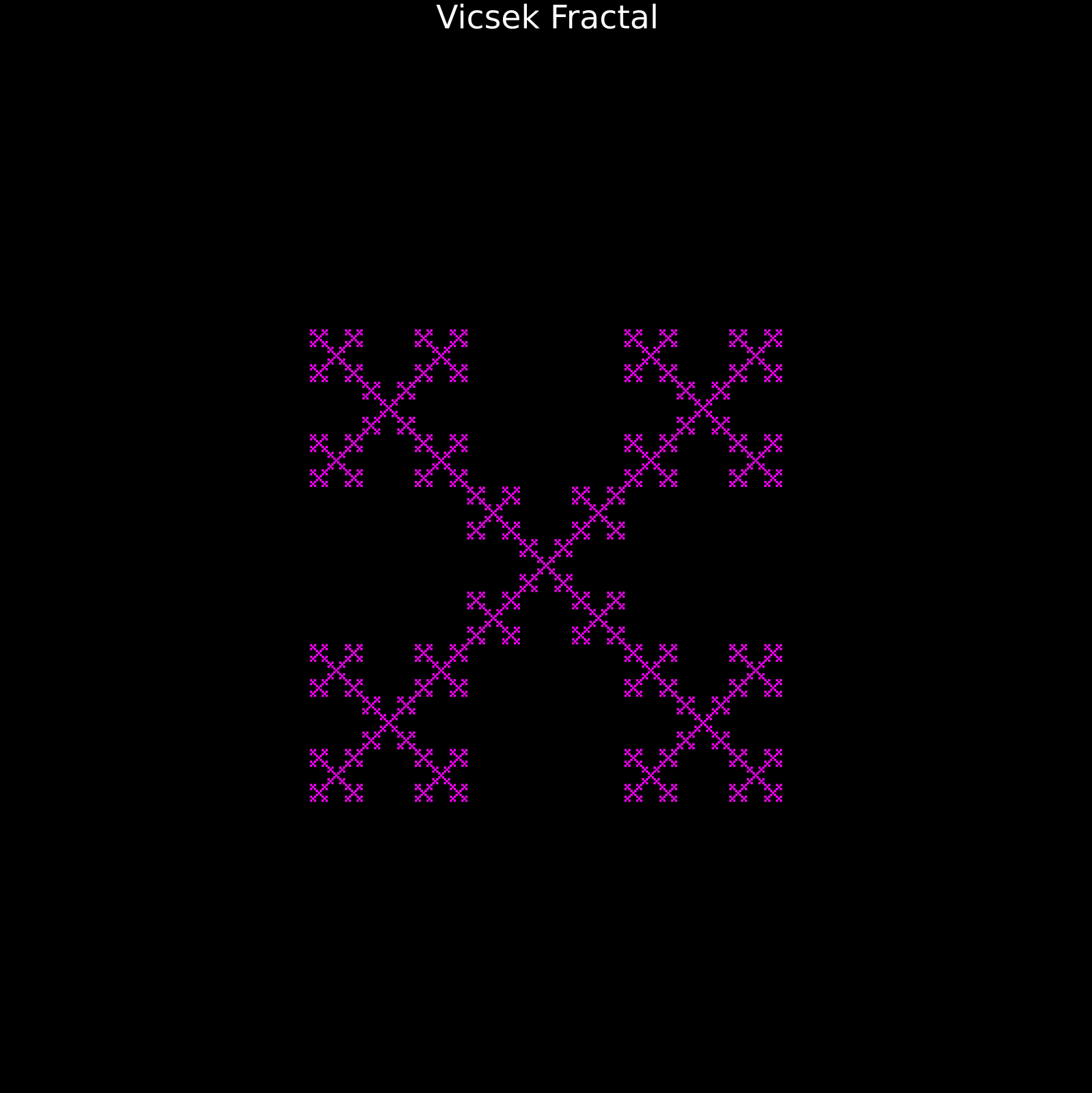

Geometric Recursion

Iterated Function Systems (IFS)

L-System Curves

Tree Fractals

Strange Attractors

Random Fractals

Cellular Automata

3D Fractals